How I chose my solar system setup (+ avoided unnecessary waste)

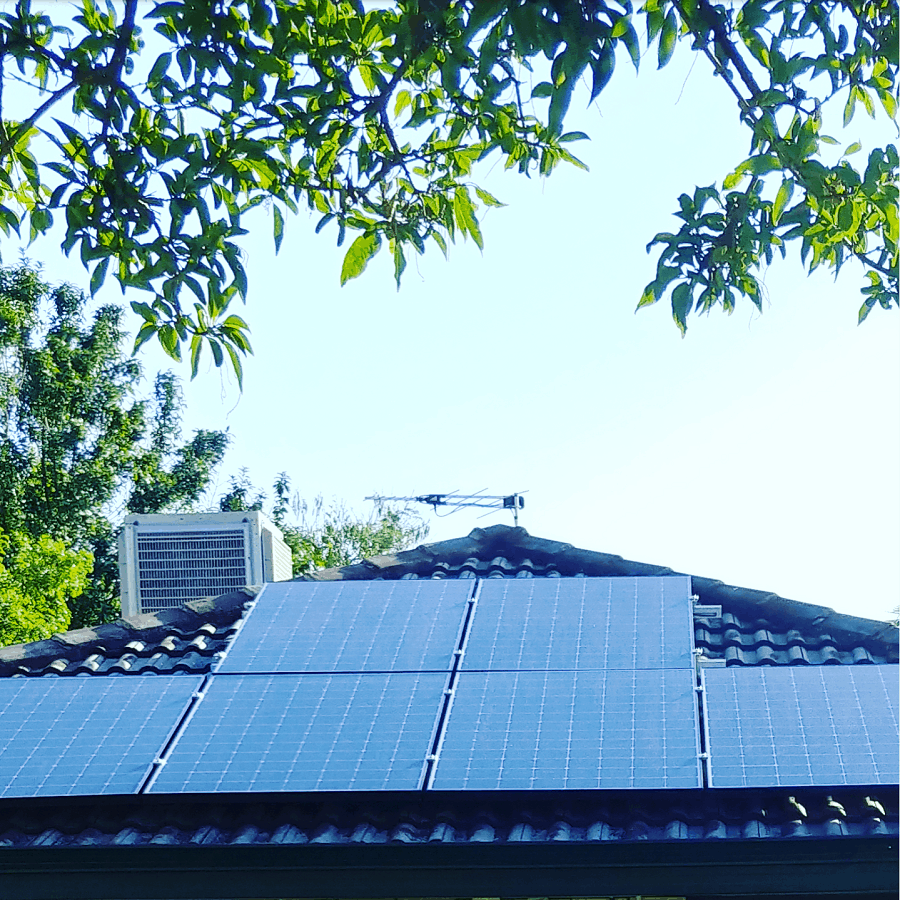

When I moved house, my number 2 priority was getting solar panels. (My number 1 priority? That was digging in the compost bin, of course!) I was pretty keen to get a solar system sorted as soon as possible, and as of Tuesday, my roof is now wearing 11 lovely panels and making me free electricity from the sun.

I posted a photo of my roof on social media, and received a few questions asking which company I’d gone with, and a lot of nervousness about making the ‘right’ choice or finding the ‘best’ company.

I get it! Solar systems might pay for themselves eventually but they are a big cost upfront, and the internet is a crowded place when looking for help and information.

I thought I’d talk you through my decision-making process, and how I came to choose the system that I have.

I’m not saying it’s necessarily right for you, but if you’re thinking about getting solar, some of the questions (and answers) will definitely be relevant.

How Solar Systems Work – An Overview

Yes, solar panels make electricity from the sun. But beyond that, it’s important to understand how they work so you can choose a system that meets your needs, and not pay more for something that’s too big. That’s a waste – of your money and resources generally.

Solar panels make electricity when the sun hits them directly. In Australia and the southern hemisphere, this is on the north facing roof; in the northern hemisphere it’s the south-facing roof. Where I live, a north facing roof will get sunlight from 9am – 3pm (ish) in winter, and 8am – 6pm (ish) in summer (the sun never sets after 7.45pm here).

So that means I can use ‘free’ electricity during those hours, but outside of that, I still need to rely on the grid (or use a battery).

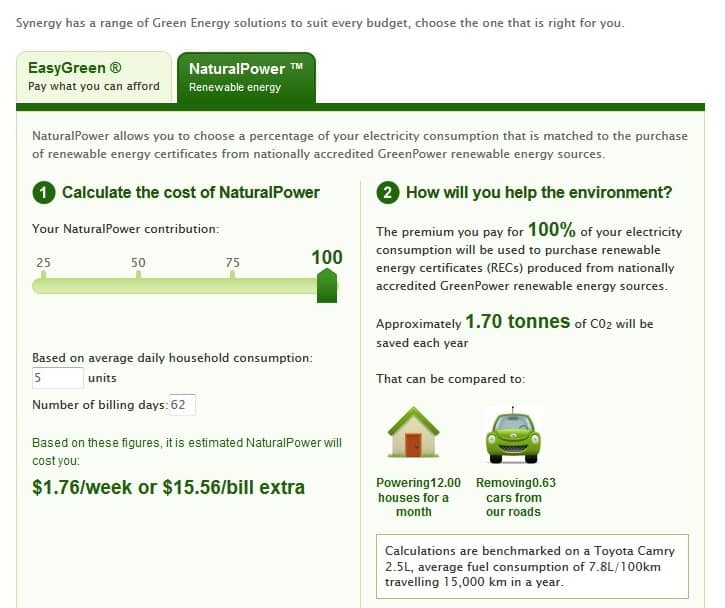

The excess electricity I produce during sunlight hours will go to the grid. Unfortunately it’s not as simple as giving electricity to the grid in the day and getting it back at night. Or at least, it’s not a simple exchange financially. I sell my spare electricity to the grid during the day for 7 cents a unit (this is called the feed-in tariff), but when I buy it back, it costs me 28 cents a unit.

Ouch.

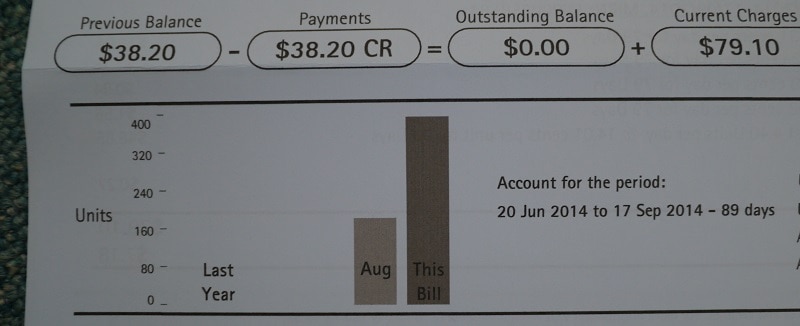

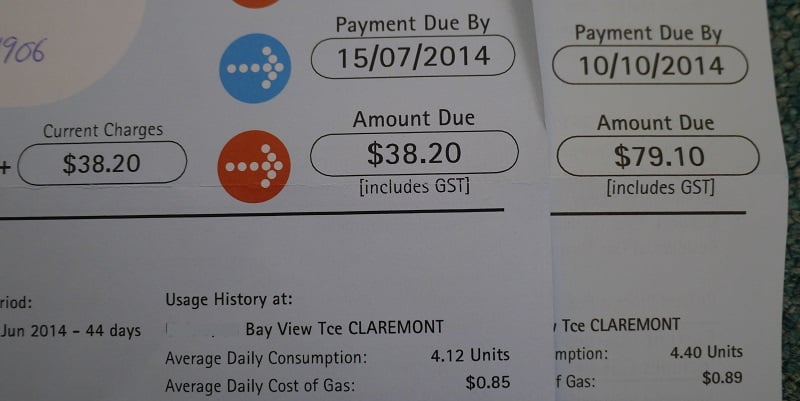

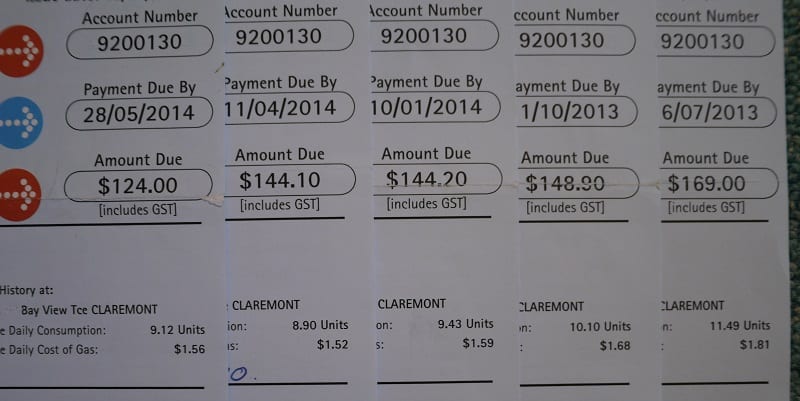

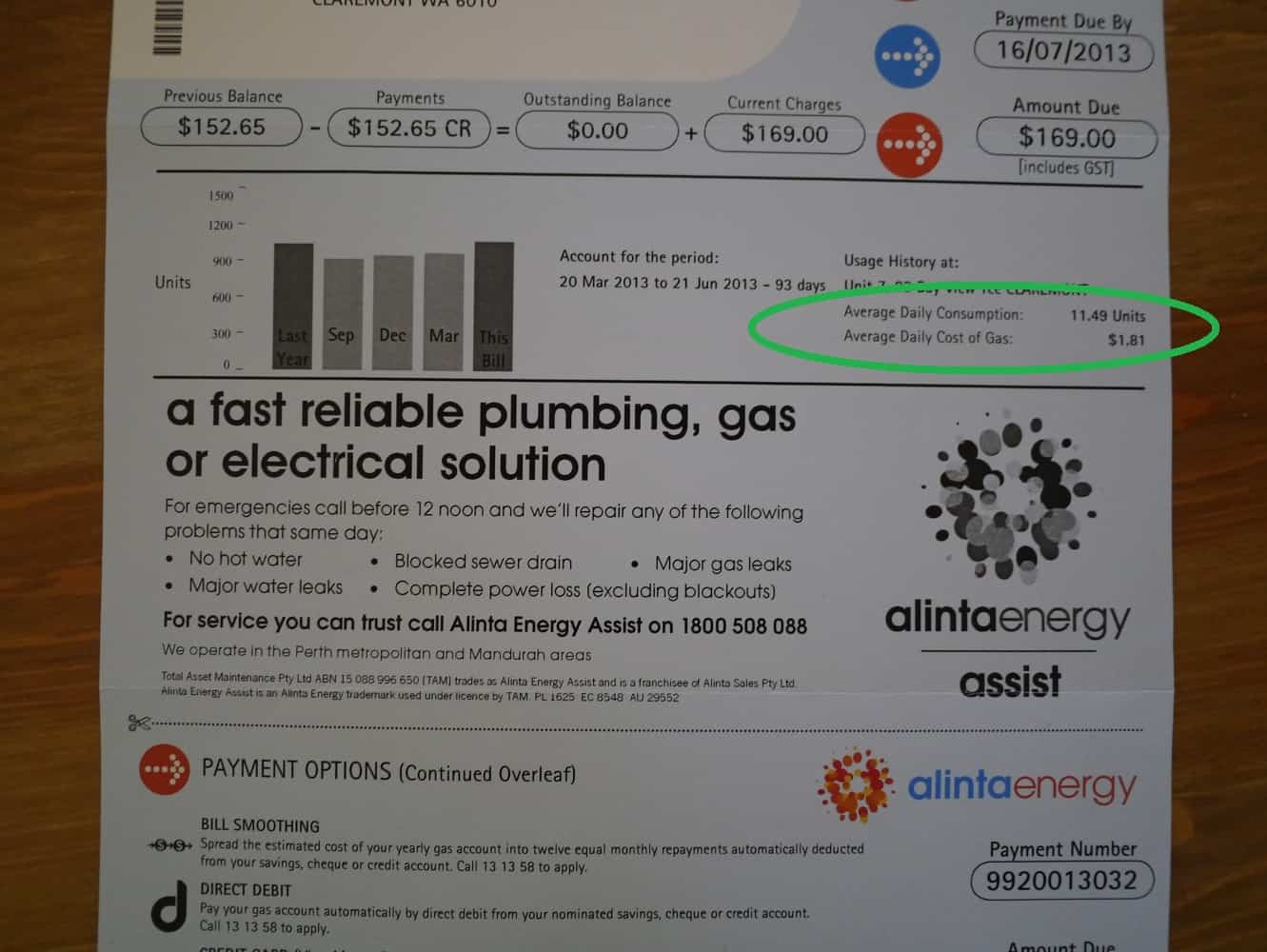

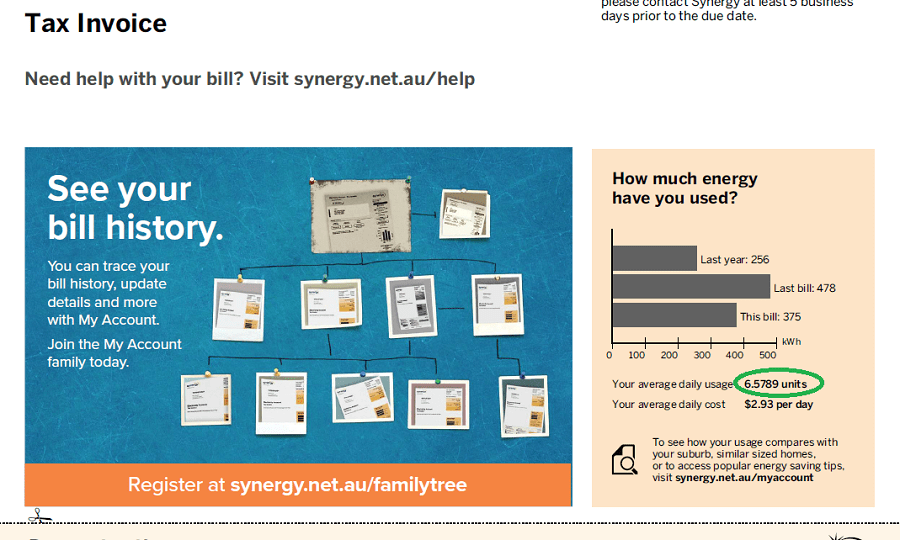

Let me explain the numbers. When you receive your electricity bill, it will tell you how many units you use every day. If you’re a low electricity user and/or have gas, you might use 5 units per day. If you have a big house, with heaps of gadgets, you’ll use more. The Australian average is 19.8 units a day. It will also vary by seasons (winter means more heating).

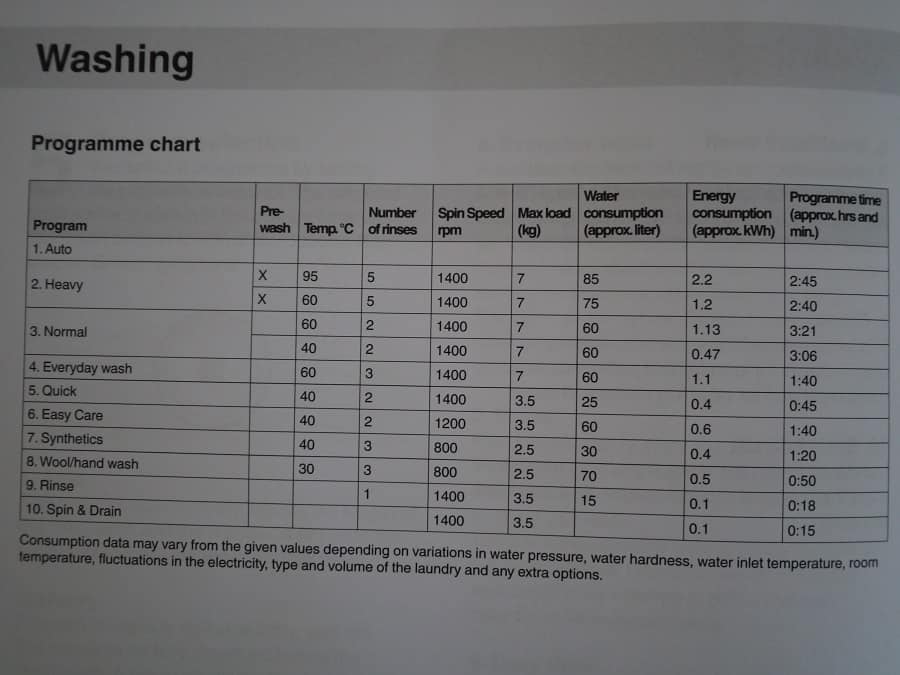

A unit is 1kWh, shorthand for 1000 watts per hour. When we talk about solar systems, we talk in kW – for example, a 1.5kW or 3kW or a 5kW system. What this means is every hour that the sun is shining, a 3kW system will produce ~3kW of power, meaning 3 units every hour.

Except this isn’t quite accurate, as panels and systems aren’t 100% efficient. In the morning or the evening they won’t crank at full power, nor if shaded, and once they reach 25°C/77°F they lose output efficiency – which can be 25%. (In Australia, panels tend to work better in spring and autumn than summer – black glass in full sun is going to get very hot very quickly.)

An average 3kW system might generate ~13 units per (sunny) day. (That’s 3 units per hour in the middle of the day, and a bit less in the early morning and late afternoon, and none that time the sun briefly went behind a cloud.)

Panels are usually 250 – 380W each depending on the brand, so 3-4 panels makes 1kW (1000 W). A 3kW system might have 10 – 12 panels.

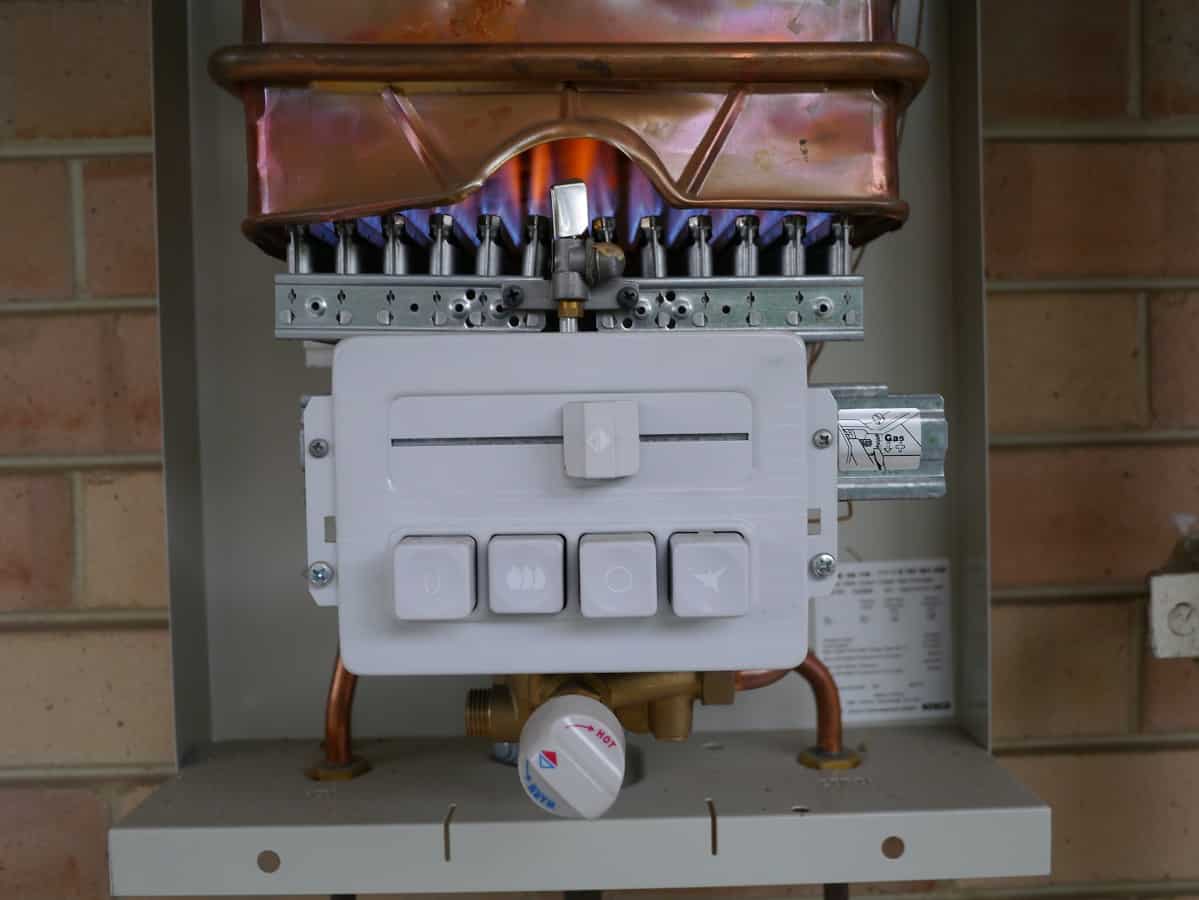

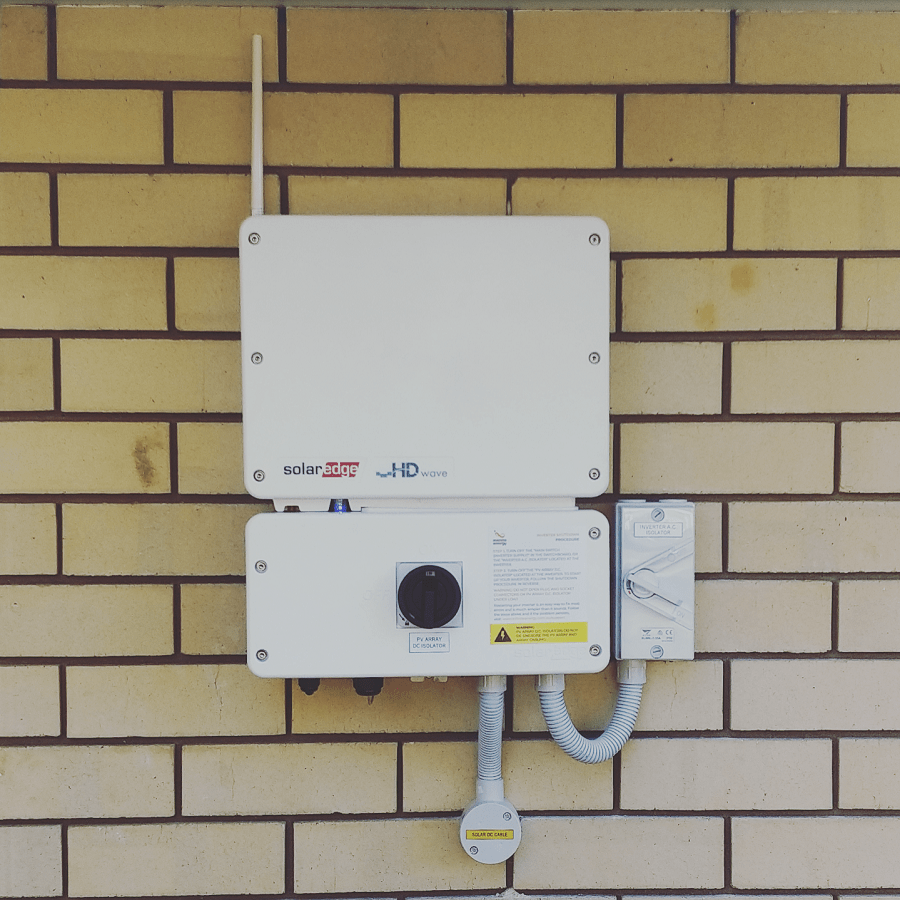

Solar systems are made up of panels, and also an inverter. The solar panels use the sun to make direct current, and the inverter changes it to alternating current that can go into the grid/fed into the home.

The inverter is the limiting component: if an inverter is 3kW it will only ever be able to produce 3kW per hour, even if you had 20 panels, adding up to 6kW.

Often the panels will go slightly higher than the inverter (for example, 3.84kW of panels for a 3kW inverter), to help offset some of the energy ‘lost’ as inefficiency.

How Big Does My Solar System Need to Be?

There are a few things to think about when choosing a solar system. These are three questions I asked:

- How much electricity do I use? (check previous bills);

- How big is the part of the roof that faces in the right direction? (north for southern hemisphere, south for northern hemisphere);

- What about battery storage?

Considering solar panels: how much electricity do I use?

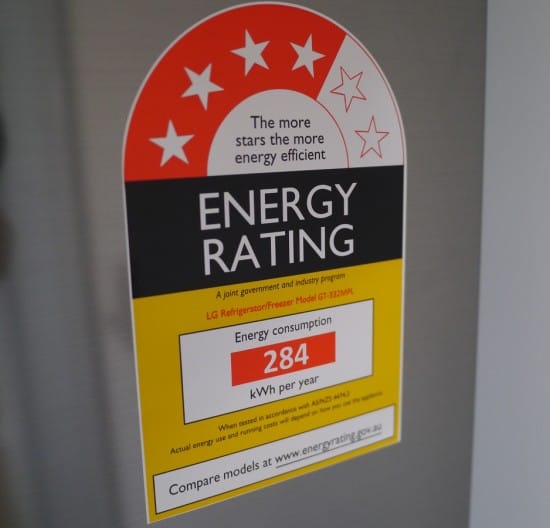

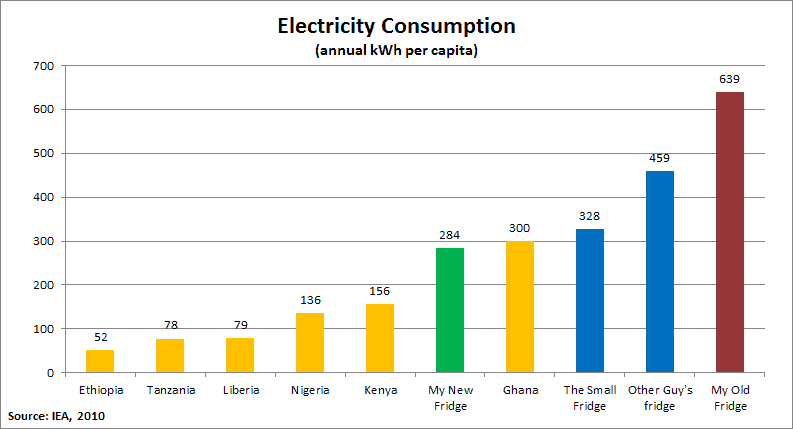

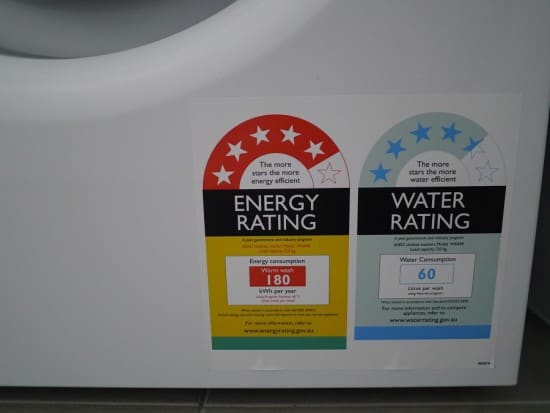

I haven’t lived here long enough to know how much electricity I use, but I know that at my old place (which had separate solar hot water and no gas) I used 5 – 7 units a day. There was no air conditioning (the building was 10* energy rated) but I did use a heater sometimes in winter months.

I’m pretty careful with my electricity use, so it’s reasonable to assume that my electricity use might be the same, or a little bit higher (this place has air-con, which I might bust out on those 40°C/104°F + days in summer).

Considering solar panels: what is the orientation of my roof, and is that optimal for solar panels?

My roof doesn’t face north, it faces north-east. The back faces south-west, and the side faces south-east (there are only three sides as it’s a duplex/semi-detached). Not having north, north-east is best (because I’m in the southern hemisphere; if you were in the northern hemisphere, south and southern variations are best). Where I live, the south-west might pick up a bit of summer afternoon sun but would be useless in winter, and the south-east would be completely useless – in theory it might pick up a bit of morning summer sun, except there are heaps of trees on that side, so it’s in permanent shade.

The arc of the sun changes over the seasons. In winter it has a narrow arc that doesn’t get as high in the sky. In summer it rises further from the east, gets higher in the sky, and sets further to the west. The exact difference changes according to distance from the equator.

Because of the shape of the roof, I could fit 11 panels on the north-east side (which would be a 3kW system). Any additional panels would go on the south-west, only getting (some) summer afternoon sun.

Considering solar panels: is considering a battery an option?

Batteries in their current form don’t make sense (to me). Take the Tesla Powerwall, which holds 13.5kW of energy and costs around $9,000. If I use 7 units a day, I could use up the entire storage capacity in 2 days if the sun wasn’t shining. Then I’d need to buy power from the grid.

So a battery wouldn’t actually mean going off-grid.

When the sun is shining, of the 7 units I use a day, 2-3 units are outside daylight hours. To buy these costs me 28 cents a unit, so less than $1 a day. If I save $1 a day by having a battery, but that battery costs me $9000 to install, it will take 24 years to pay it off.

As a small user of electricity, I’m currently better off buying my evening electricity from the grid (well, if I actually had $9,000 to spend on a battery, which I do not).

Isn’t a bigger solar system ‘better’?

It’s easy to think that a bigger system is better. But that isn’t necessarily the case.

The issue is, most of us want to use at least some electricity when it’s evening, night time, overcast or raining. A bigger system isn’t going to do anything differently if there is no sun.

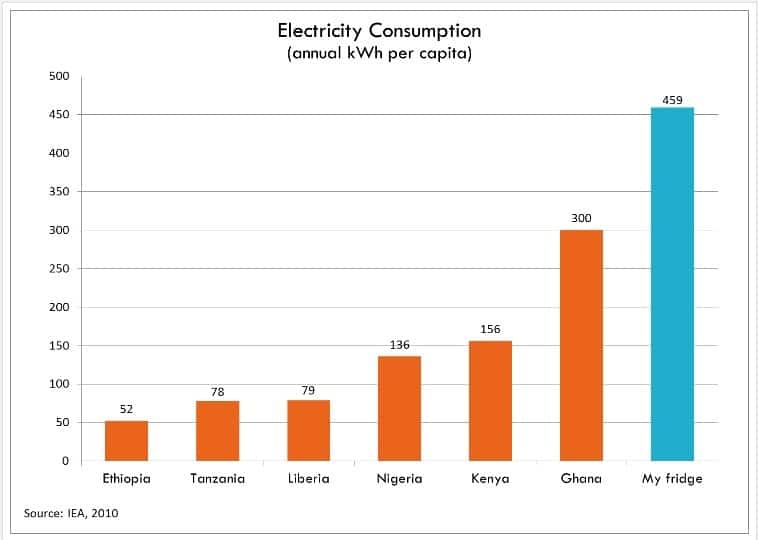

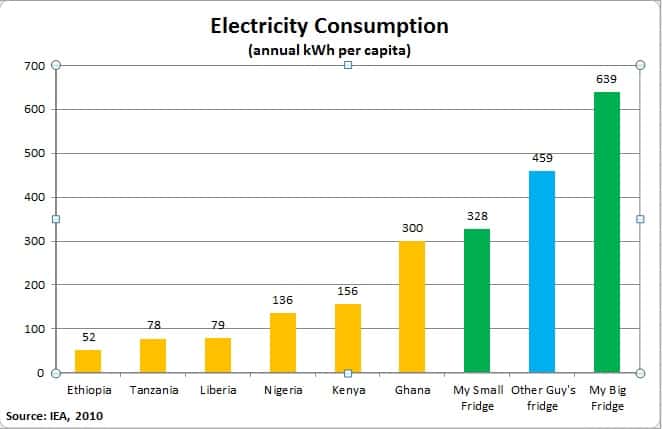

What about producing excess in the daytime? As I mentioned, I can sell my electricity back to the grid for 7 cents. That’s better than nothing, but it’s not a route to riches. Say I have a 3kW system that generates 13 units a day and I don’t use any of them (unlikely, as I keep my fridge plugged in even when I’m away).

Selling all 13 units to the grid, I’d make 91 cents a day.

The reality is I’ll be using some of that myself, and when I need electricity in the evening, I buy it back at 28 cents. If I use 2-3 units in the evening, that’s my 91 cents gone.

That might seem cost neutral. Except, where I live, I also have to pay a connection fee to the grid: it’s $1.03 a day.

(The connection fee is also a tax on people who can’t afford solar panels. In 2014, it was 36 cents a day. As more people get solar panels, the electricity company needs to get money elsewhere, so it tripled the supply charge. The people who lose the most are renters and those who can’t afford solar panels.)

So I may be able to sell electricity to offset my evening usage, but I’m still paying $1 a day in service fees.

If I wanted to offset this cost, I’d need another 3kW of panels, generating another 13 units of energy a day.

Except, then there are those days when it’s overcast, or it rains. Those days don’t make any units, so there needs to be more panels to cover this.

Once you get more panels (which cost more) you also need a bigger inverter (which costs more). Not to mention more (correctly oriented) roof space. This extra cost might pay itself back over several years, but the prices for buying and selling electricity and the connection fee costs aren’t guaranteed, and could change.

If the government changed its mind about allowing customers to sell their excess back, I wouldn’t get anything for what I didn’t use.

It makes more sense to get the smallest system you need to generate the power that you actually use, rather than going bigger and then selling the excess back to the grid.

I know for me, a smaller system means I will be more careful with the electricity I use. A bigger system would encourage me to be more lax, choosing less energy-efficient appliances, perhaps.

How to choose a solar system that lasts (and continues to work)

At my previous address, I had solar panels (installed when I moved in). After 18 months, they stopped working. There was no power to the inverter. I called the builder, who told me the developers had decided to organise the solar panels themselves because they were cheaper, and that the company they had used were going to be hard to chase up and that I would need to call them every day.

Which I did – to their call centre in India – for 8 months. When I moved out 18 months later, the panels were still not fixed, despite having a warranty on parts and labour.

This time I was very clear I was using a company that was based in Australia, with a local office I could call and a good reputation. I also wanted to ensure that the panels and the inverter I had were made by a reputable company, and had some kind of warranty.

Paying less money for a system that breaks and then cannot be fixed is not a good deal, in my mind.

Many panels have a 10 year warranty, however a few have a 25 year warranty (for performance and the product itself). We all know that things like to break the second they are outside the warranty, and I don’t want to have to replace the system and buy a whole other set of panels in 10 years.

Also, panels lose efficiency every year, and conventional ones may operate at only 80% in 25 years. Better ones guarantee higher returns.

Good inverters also come with a warranty: the longer, the more reliable you’d expect the inverter to be.

My solar system: what I chose

I chose a 3kW system (with 3.96kW of panels and a 3kW inverter). I think I could have made do with slightly less (maybe 2.5kW), but my roof is north-west, not true north, and being able to run the air-conditioner in summer is a privilege I’m looking forward to.

The panels have a 25 year performance and product warranty and the inverter has a 12 year warranty. With the savings made on my electricity bill, the system will have paid for itself in 6 years or so.

A top-end 3kW system actually cost the same as a mid-range 5kW system. Whilst it seems tempting to go for bigger, I knew that system was more than I needed and half the panels would only make electricity for a few months of the year (they’d have to go on the back roof). Choosing a system that’s guaranteed for 25 years (although I may have to replace the inverter) was more appealing.

For those interested, the company I used to install my solar system is Infinite Energy (the link is a refer-a-friend link, but I wasn’t paid or given any kind of discount to write this post). As I’ve only had my system for 2 days, I can’t speak about the longevity of the system (yet!) but to date, they’ve been helpful, efficient and quick in getting everything set up. So yes, based on what I know I’d recommend them.

Now I’d love to hear from you! Do you have solar? How do you find it works for you? Are you thinking of getting solar? Is anything is putting you off (aside from saving up the initial cost)? How do the feed-in tariffs work (or not) where you live? Any other thoughts? Please share in the comments below!