Not buying it: 5 tips for buying less stuff

The world doesn’t have a recycling crisis, it has an overconsumption crisis. These words (by my friend Oberon, author of the book The Family Guide to Waste-Free Living) ring true to my ears. Sure, we need returnable packaging and reusable products and fixable items, single-use items that compost, products that are designed to last, and circular models that keep items in use.

But even this is not enough, at our current rate of consumption.

We* need to be buying (and using) less stuff.

(I say *we as a society and a global community, recognising that within this there are plenty of people for whom this does not apply: those that do not have the resources to buy what they need, let alone more than they need; and those who already conserve all the resources they can, as two examples.)

Buying less stuff sounds easier than it is, for many of us. It’s so easy to buy stuff, and there is so much (beautiful, clever, thoughtful) stuff out there to buy.

And we know about it because our screens show us all of this fantastic stuff, in the way of social media feeds, adverts and articles. We receive emails. We see it in stores, we see it in catalogues or flyers.

We don’t even need to have the money to be able to buy the stuff we see. Credit is freely available. Buy now, pay later.

In a world that makes it so easy for us to buy stuff, and makes stuff that is so desirable, it is hard to say no.

But if we want to live in a more equitable and sustainable world, we have to learn to say “no” more. A lot more.

It’s not the cool opinion, of course. The more attractive (and marketable!) option is to persuade us to buy a bunch of shiny ‘sustainable’ stuff and encourage us to feel good about our choices.

But we can’t consume our way out of the issues we’re facing as a society and as a planet.

So in the face of all this advertising and all these beautiful things, how do we buy less stuff?

Stem the flow of advertising

What we don’t know about, we can’t buy. The less adverts we see, the less we’ll be tempted to buy things.

- Unsubscribe from all store newsletters. Everything is on sale of the time, products are constantly being upgraded and when you’re truly in need of something, you can go to them, rather than letting them come to you.

- If unsubscribing from everything feels like too much, choose the companies you spend the most money with, or the companies you tend to buy stuff from that you don’t actually use. Or even just the ones you don’t buy from anyway. Every single unsubscribe means less adverts, and less adverts mean less temptation.

- Install an adblocker on your laptop, desktop, tablet and mobile. I use Adblock Plus on my laptop and Adblock Browser on my phone. (Both are free.) They stop all those in-feed ads appearing in articles, and side bar ads appearing on computer screens.

- When looking at online stores, use a private browser. That way you won’t be tracked. The store won’t ‘remember’ what you were looking at, and you’ll get less sponsored ads in your social media feed showing you exactly the thing you were looking at two minutes ago, trying to wear you down.

- Put a ‘no advertising material accepted’ sticker on your mailbox, to avoid receiving catalogues. Get in the habit of putting unaddressed items straight in the recycling bin rather than bringing them inside. Anything that gets mailed to you can be returned unopened – cross through the address and write “not at this address, return to sender and remove from mailing list” on the packaging, and pop in the post box.

- Unfollow pages, businesses and people on social media that spend most of their time selling to you.

Mindset matters

Honestly, mindset must be the hardest part. It’s very easy to talk ourselves into the idea of buying stuff, whether convincing ourselves that we “need it”, making the case that it’s a ‘reward’ for a difficult week, or just sheer stubbornness: “why shouldn’t I buy it?”

Needs versus wants

Distinguishing between ‘needs’ and ‘wants’ can be challenging, particularly when the stuff is inherently useful. But useful is not the same as necessary.

One of the most useful questions to ask, is “did I go looking for this particular item to solve a problem I have, or did this product come to me offering to solve a problem I didn’t even know I had until I saw the product?“

Example 1, looking to solve a problem.

“My coffee plunger leaks when I pour it, and drips coffee all over the kitchen bench and my shoes and drives me crazy every morning. I’m going to look for a leakproof, drip proof version that doesn’t make me want to scream at breakfast.”

(Of course, problems are subjective and what’s a dealbreaker for someone is simply a mild annoyance to another. That’s not our place to judge. My coffee plungers drips everywhere and it infuriates me every single time I make a mess, but not enough for me to actually replace it. That doesn’t mean everyone would put up with it.)

Example 2, when the ‘solution’ comes to you.

“That kitchen draining organiser rack in this sponsored ad is so clever! It keeps everything so neat and tidy. My own dish draining rack is usually quite chaotic, come to think of it…”

I saw an ad just like this, and the product was clever. But ultimately it’s more stuff cluttering up my place, and another thing to store. Plus the main reason my dishes create so much clutter is because of the volume. (Reusables = dishes.) A dish rack isn’t really going to solve the problem.

We’re much more likely to make better decisions when we actively try to solve a problem, rather than passively letting adverts solve problems for us, which blurs the line between ‘need’ and ‘want’.

Stew on your choices

A useful way to distinguish between needs versus wants is simply to wait, before making a purchase.

How long (and whether) you wait depends on what it is and how much you need it, but assuming it’s a non-emergency purchase, 30 days can be a good length of time.

Did waiting increase your resolve to buy it, and reassure you that this is definitely something that you want to buy, did you realise you could make do with something else, or did you actually just forget about it altogether?

And if you feel like you can’t stew on this choice, because it’s a limited time offer, a sale item, there’s only one left, etc etc, remember that this scarcity marketing is a deliberate tactic that companies use to make us buy stuff.

What would it actually mean and what impact would it have on your life if you waited and the product was no longer available?

Only you can answer that, but it’s definitely a question worth asking.

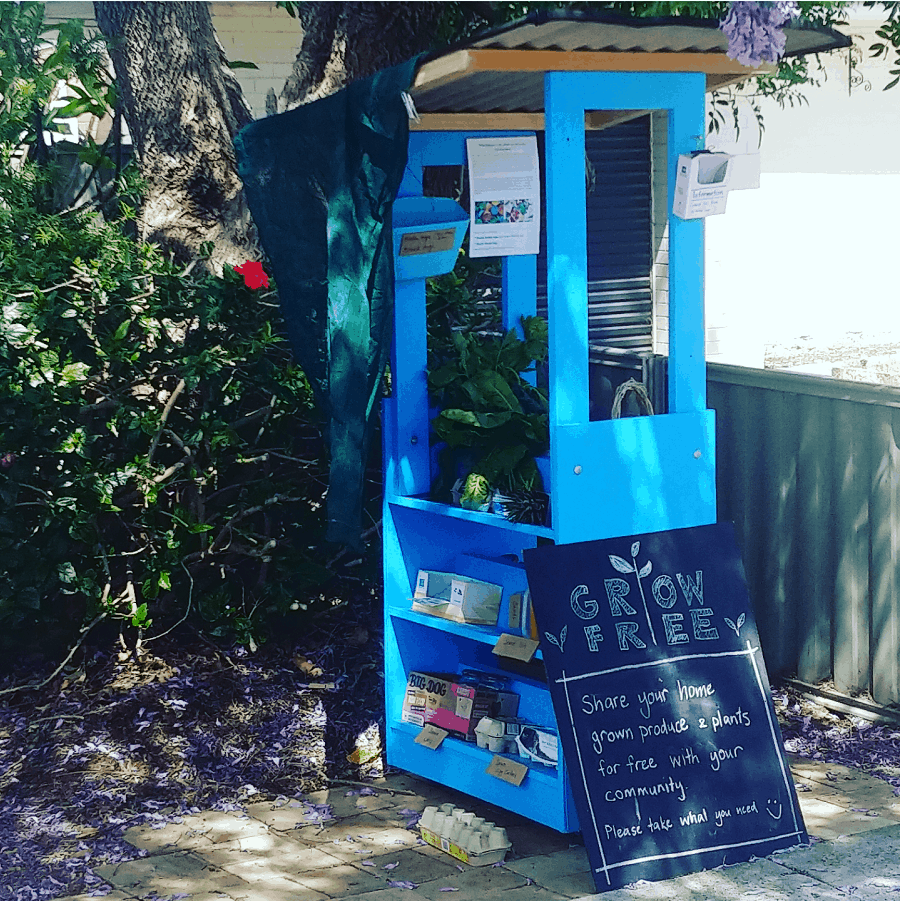

Find a new reward that isn’t stuff

If you’ve ever gone shopping to cheer yourself up, or bought yourself stuff as a reward for a difficult week, finding a different reward that doesn’t require shopping can be helpful. This isn’t about deprivation or going without so much as filling the gaps with something else.

As a starting point, switching from buying ‘stuff’ to buying consumables (artisan soap or fancy chocolate, for example) can help. We’re not breaking the habit just yet, but we’re shifting it to something that doesn’t involve the accumulation of stuff.

An alternative could be to use your need for a shopping “fix” to buy some pantry grocery items, and donate them to a local food bank.

But the best way to avoid stuff is to find other ways to make ourselves feel better that do not require shopping, or going to the shops.

Taking a walk, listening to a podcast, taking a long bath, going for a run, swimming, picking up litter, reading a library book, playing an instrument, baking, learning a new skill, or something else that brings joy and peace and a sense of satisfaction.

Challenge your ‘not buying it’ muscle

Habits get stronger the more we do them. If we’re used to buying stuff, it’s going to be hard to change gear. But the more we don’t buy stuff, the better we get at it.

One way to reinforce the ‘not buying it’ habit, especially at the start, is to take a challenge. You want to pick something achievable – not buying anything ever again is probably a bit extreme. You could try buying nothing, or simply focus on no new clothes, or start by working on buying nothing new (so second-hand items are allowed).

Or you could challenge your idea of ‘enough’ – for example by deciding to only wear 3 outfits for a month, or only cooking meals that require one pan.

- Choose a challenge and set your rules, including any exceptions you want to include.

- Choose a timeframe: do you want to try for a month? Longer?

- Choose a reward for the end of the challenge that isn’t ‘stuff’ and ideally doesn’t involve spending. This helps rewiring your brain that buying stuff = reward. (You don’t need to only reward yourself if you’re ‘successful’ either – reward yourself for giving it a go.)

- Did you want to challenge a friend to join you? It can make it more fun if there’s someone else to share the pain with, and there’s nothing like some friendly competition to keep on track.

- Set aside some time at the end of the challenge to reflect. What worked well? What was hard? How did we feel? Were there any obvious stumbling blocks? What would we do differently next time?

If you struggle, cave in or make mistakes, pay attention to them. They are telling you how to do better next time. If your weakness is Fridays after work, fill that timeslot with another activity to stop you shopping. If you notice that social media encourages you to buy stuff, think about how you can change your usage to reduce this.

Accept that change isn’t easy, but it’s worth it.

Change isn’t easy, nor is it a straight line. But buying less stuff doesn’t have to feel like going without. It’s simply shifting priorities. Making room for stuff that isn’t ‘stuff’.

Buying less stuff means less strain on resources (both the earth’s natural resources, and your personal bank account).

Buying less stuff means you can reduce your debt, or start saving for stuff that really matters.

It frees up the time you spent online browsing, and at stores, to do more enjoyable and meaningful things.

Less stuff more us means more stuff for others. It’s more equitable.

It keeps your house less cluttered. There’s less to sort, and less to tidy. And less to declutter when you realise all that stuff you bought isn’t being used.

When you buy less, you can buy better. The reason I can afford to buy ethical and sustainable items, when I actually need them, is because I buy less overall. Buy less, choose well, make it last.

Now I’d love to hear from you! Do you struggle with resisting the urge to shop? Is there anything in particular you have a weakness for? Are you a master of not buying stuff? What are your secrets? How has your relationship with shopping and stuff changed over time? Anything else you’d like to add? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

[leadpages_leadbox leadbox_id=1429a0746639c5] [/leadpages_leadbox]