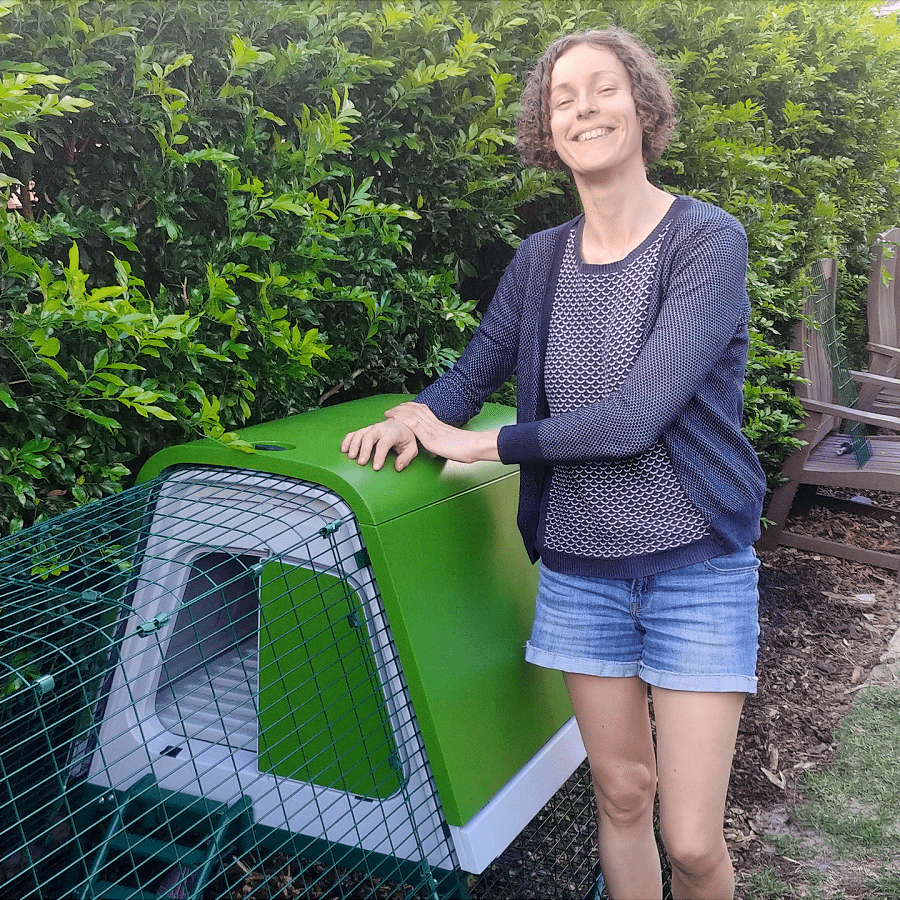

Keeping chickens: an Omlet Eglu Chicken Coop Review

This post is a collaboration with Omlet.

If there is one thing that’s unexpectedly brightened up my 2020, it’s chickens. Adopting chickens back in February was (probably) the best decision I made this year. These adorable, quirky little birds are just bursting with personality, and I really can’t imagine being without them.

And now I’m ready to improve my set-up and expand my flock.

Chickens like to be with other chickens… except when those chickens are new, or sick. In which case, chickens like to decide to demonstrate who is boss by mercilessly attacking the other chickens. (Eventually, a new status quo is established, but it’s pretty brutal in the moment.)

Back in February I started out with 4 chickens, but Billina sadly died of old age in September. She was sick off and on for the last few months, which involved quarantining (in a converted cardboard box in my office) and then reintroducing her to the flock a number of times – and in the space of just a week she’d go from accepted member of the family to UNPRECEDENTED THREAT.

Which was all a big drama for everyone.

And she wasn’t the biggest fan of the cardboard box (as soon as she started feeling better, she let me know).

The good news is, she lived out her very last days as a happy chicken hanging out with her friends, but it got me thinking about having a better future setup for new, sick, injured or possibly even broody chickens.

(Aside from the chickens-fighting-with-other-chickens factor, it is good practice to quarantine new chickens from existing chickens to reduce the chances of passing on diseases to one another).

Long story short… I decided a chicken tractor would be a useful addition to my setup.

A chicken tractor isn’t an actual tractor, it’s a moveable chicken coop lacking a floor. They are called tractors because the chickens dig up the top layer of soil – and then they can be moved to another area with fresh grass and bugs to eat.

Chicken tractors are often a rectangular or A frame design, with a shelter/house section. They are are great for:

- Quarantining sick, injured or new chickens;

- For mumma chickens to raise their baby chicks;

- To allow chickens to graze a particular patch of garden whilst stopping them get access to those bits they are not supposed to be grazing (like the veg patch).

They can be used as temporary or permanent accommodation for chickens, depending on how often the tractor is moved, or whether the chickens are also allowed some free-ranging time and space.

Traditionally they are made of wood and wire, I’ve also seen some made entirely out of metal – and then there’s the Omlet options, with the houses made out of plastic and the runs made out of metal mesh.

Why I opted for an Omlet Eglu chicken tractor

There are a few reasons why I prefer the Omlet option over the other options.

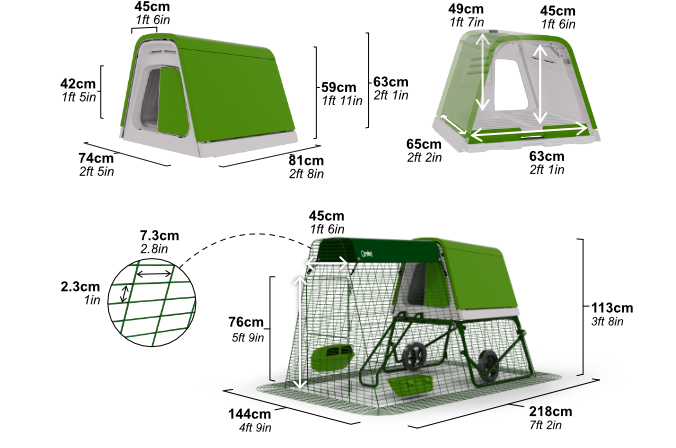

- Omlet make modular products, which gives them flexibility. My chicken tractor is an Eglu Go UP, which means the house is raised off of the ground – but it can be removed from the frame for ground dwelling. This makes it suitable for chicks (who are too small to climb up stairs), and also quail… and even rabbits. Being modular, it can also be dismantled for storage.

- You can add components or remove them according to your needs, such as extending the run, or removing the wheels, or adding handles. They also sell spare parts – something I always check for.

- The plastic house part is insulated, which makes it more suitable for the Perth climate than a metal house, which could bake the poor chickens.

- It also packs down reasonably easily. Whilst I wouldn’t say it flatpacks, it is easy to disassemble for storage if required as opposed to a rigid structure that’s moveable – yet also permanent.

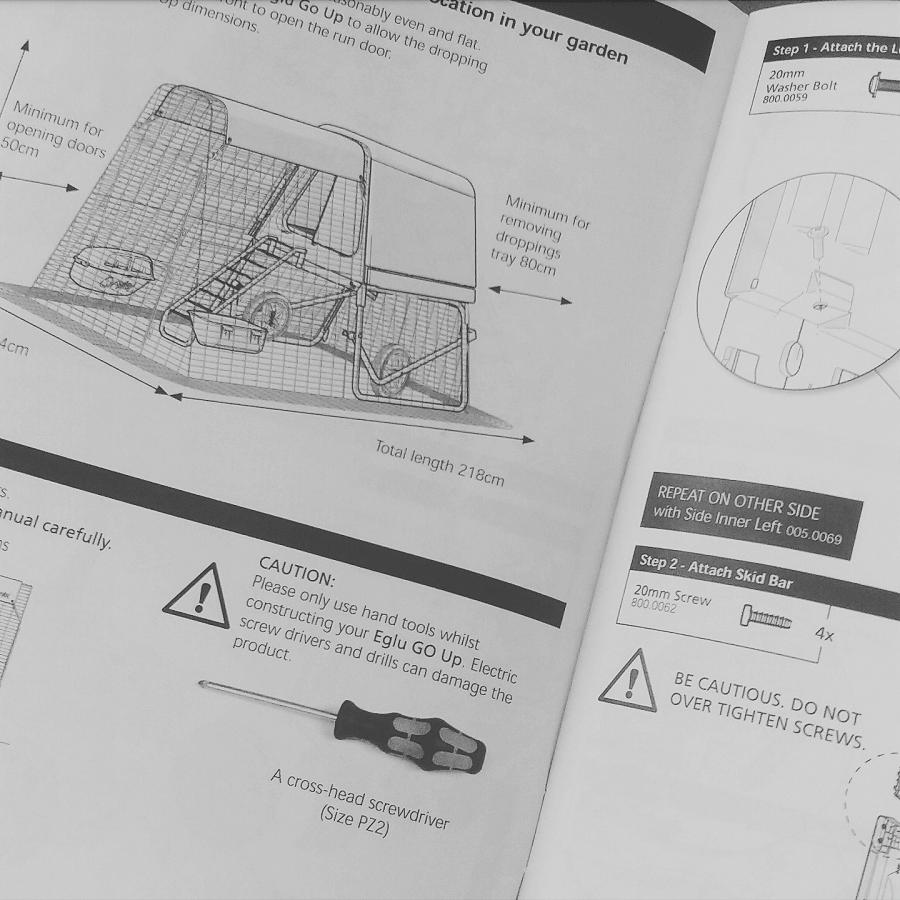

- You only need a hand-held screwdriver to assemble – hurrah! I have zero DIY skills to build a wooden A frame chicken tractor. (I do feel a bit of shame about this, as I’d love to be some kind of handy upcycler, but it is not me. I would have no idea how to start putting one together from scratch.)

- Being plastic, the Omlet is super easy to clean and completely weatherproof. Wooden chicken coops get covered in poop, and wood is not easy to clean. If I’m using it to quarantine sick birds, this is not ideal. Wood also needs to be treated every year to stop it deteriorating. And wood can harbour red mite – a chicken pest.

Omlet Eglu Go UP – a review

Omlet sent me one of their Eglu Go UP chicken coops to review, and also provided me with a 10% discount code to share with you (the code is TREADING10) – which will work on their Australian, UK, Irish and USA sites.

Omlet have three different chicken coops:

- the Eglu Go: the original Omlet chicken coop which sits on the ground and is attached to a fox resistant run. Can house between 2 and 4 chickens, depending on the size of the breed.

- the Eglu Go UP [this is the one I chose]: the same Eglu Go house, but raised on a frame (it’s accessed by a ladder) which allow the chickens to go underneath.

- the Eglu Cube: a bigger and squarer chicken coop, also raised on a frame – big enough for 10 small chickens, but too big for me and my needs.

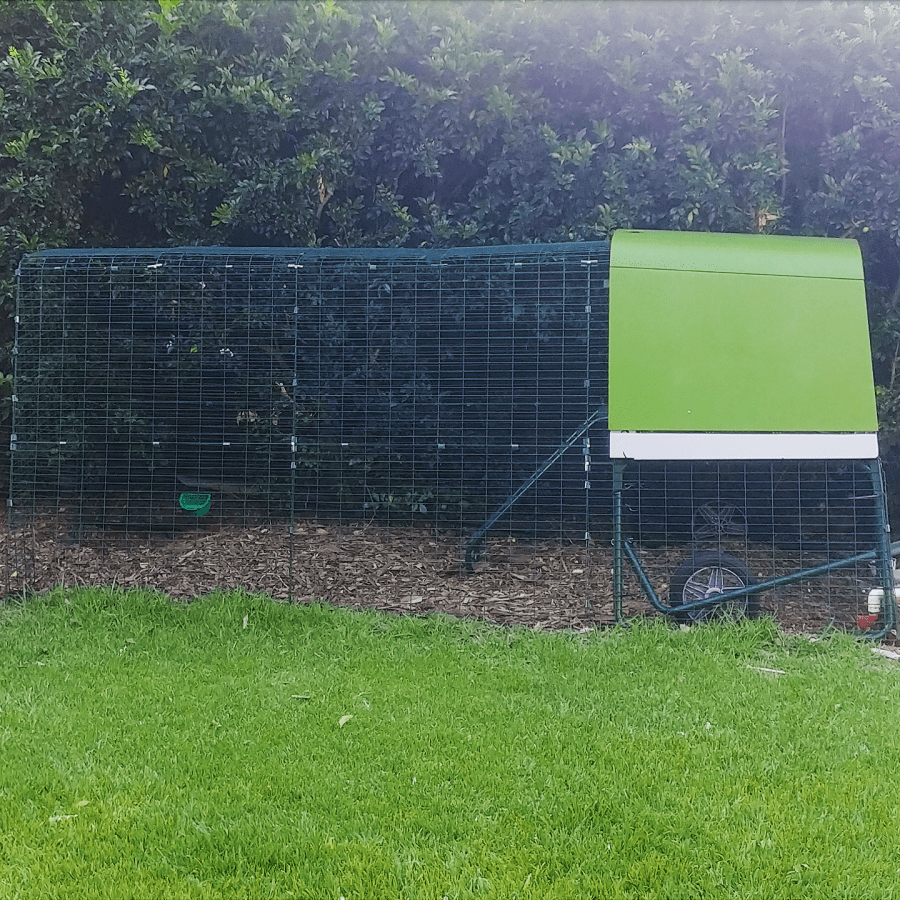

I chose the Eglu Go UP because Perth is a hot climate, and the space under the raised house provides a nice shady spot to dust bath. Also, by raising the house off the ground, and allowing the chickens to roam underneath, the same roaming space has a smaller footprint, making better use of the space and takes up less garden.

What I love about the Omlet design though, is that if I changed my mind later on, I could simply take the house off of the frame, and place it on the ground. (I’d need to modify the run to make it compatible with the house – and close the gaps, but that’s not too hard.) I’ve thought about getting quail in the future, and the Omlet Eglu Go is ideal for quail when placed on the ground (they don’t do ladders) and with the perch tray removed.

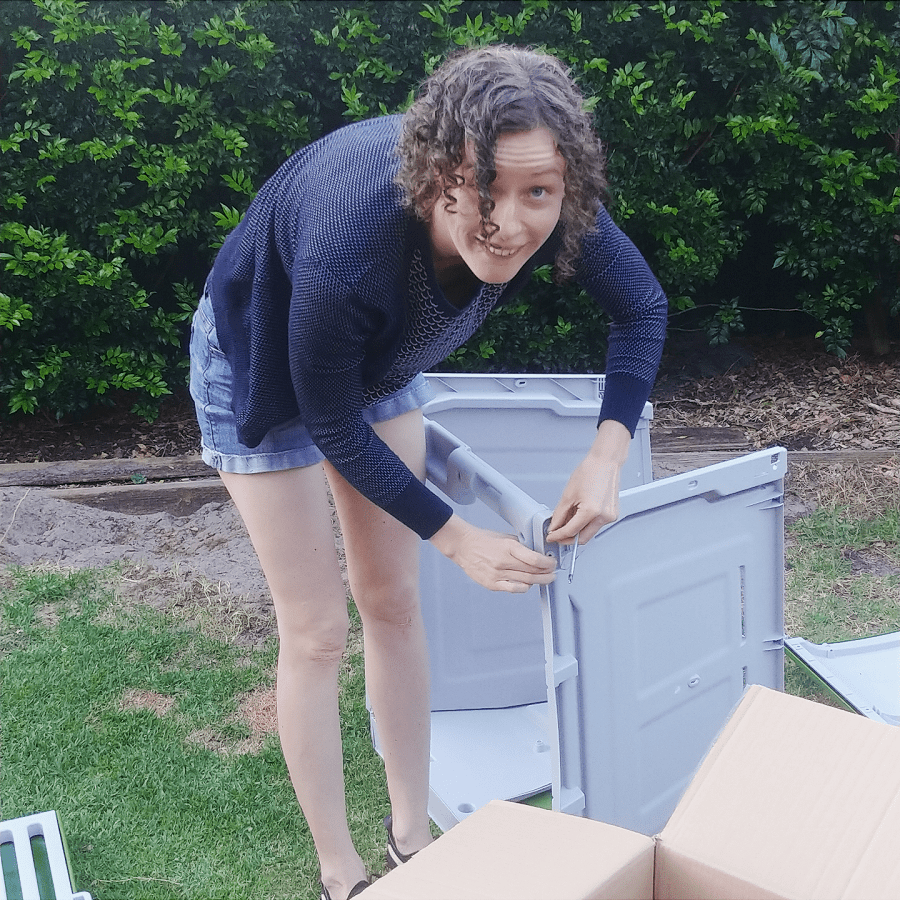

Setting up the Omlet Eglu Go Coop

Predicted setup time (according to Omlet): 30 mins; actual setup time (according to me): 50 mins.

Tools required: a handheld screwdriver.

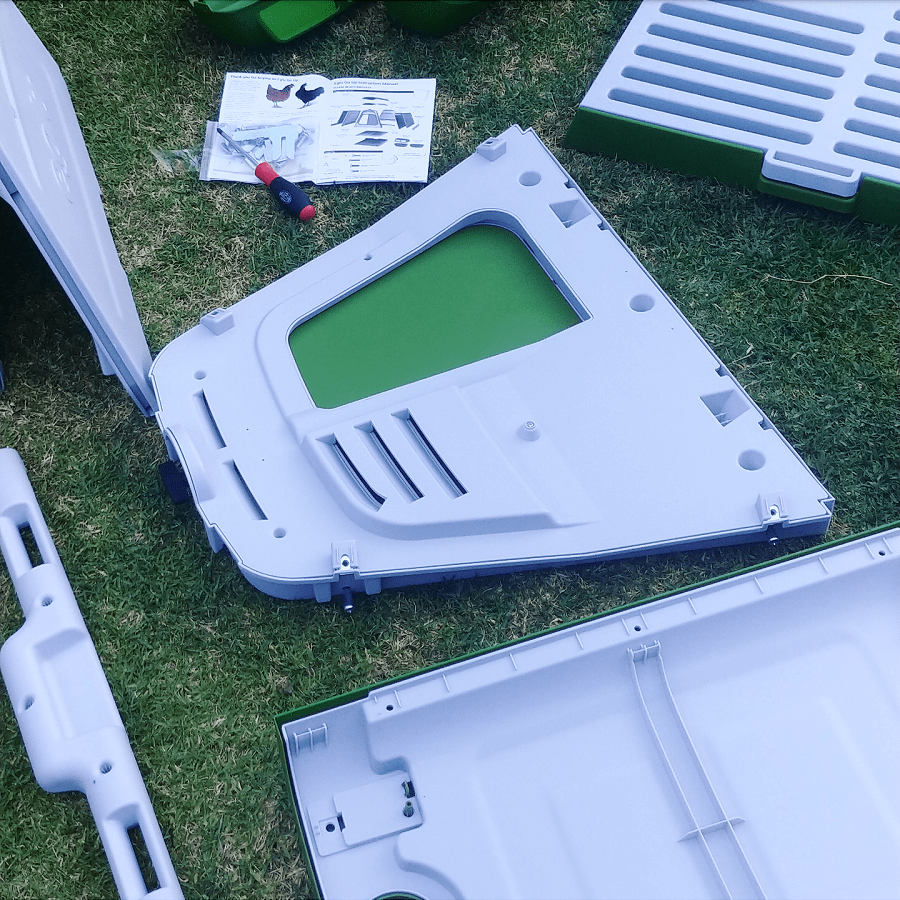

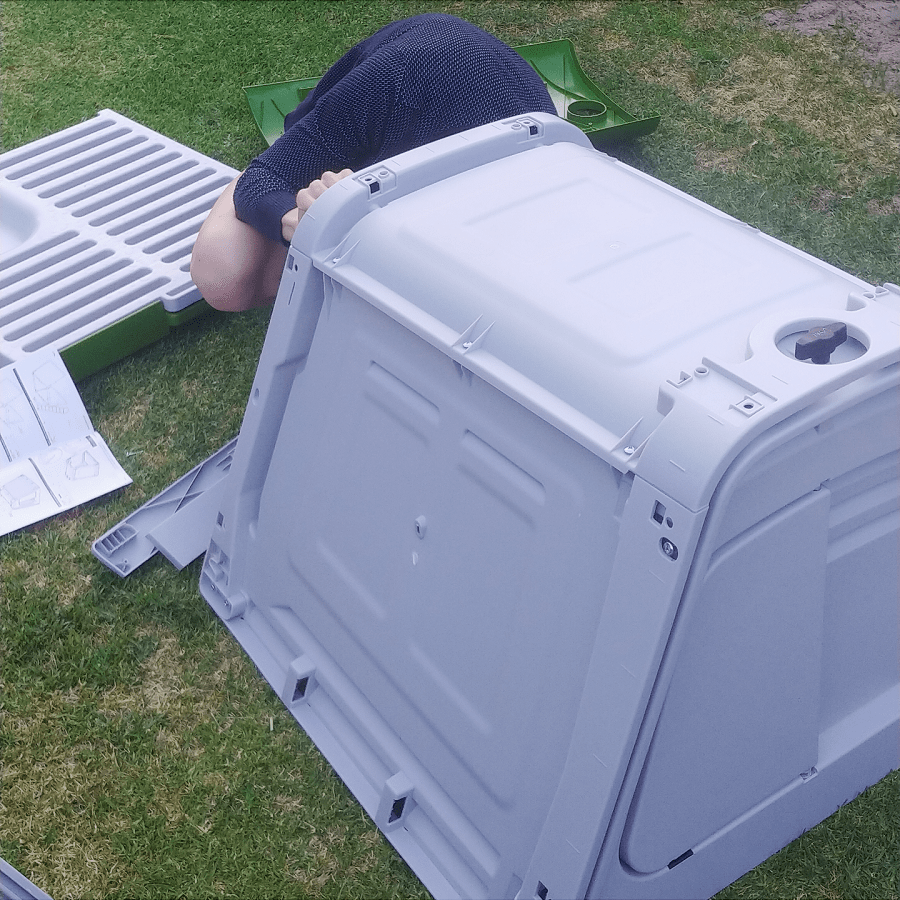

The house comes flatpacked as a series of panels, with some metal screws included to hold it all together. No polystyrene in the box, hurrah!

(The run comes in a separate box.)

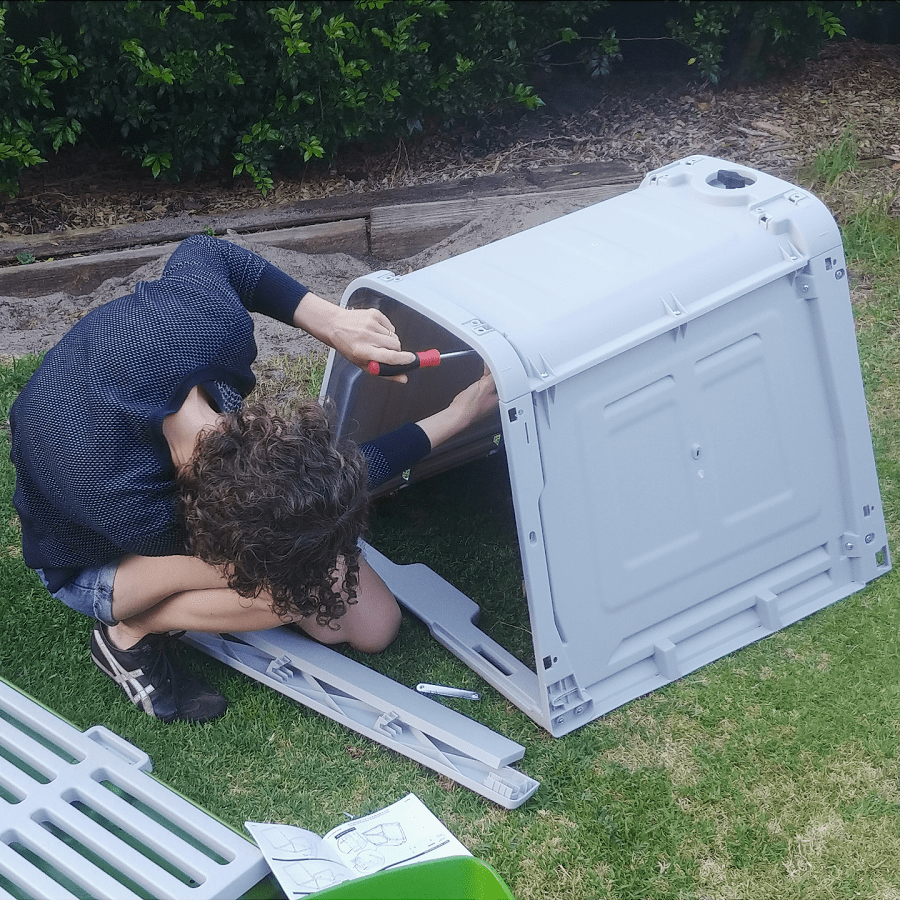

The instructions were great, really detailed and easy to follow – although I did have to check everything fifteen times, which is why it took me longer to set up than expected.

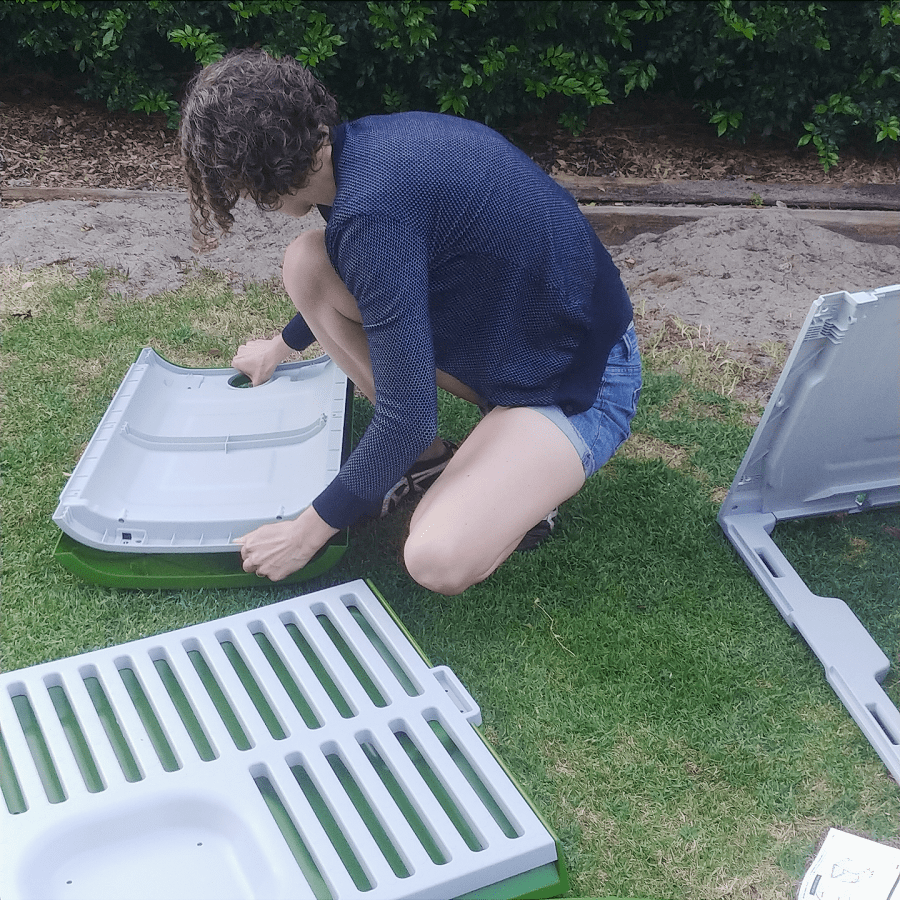

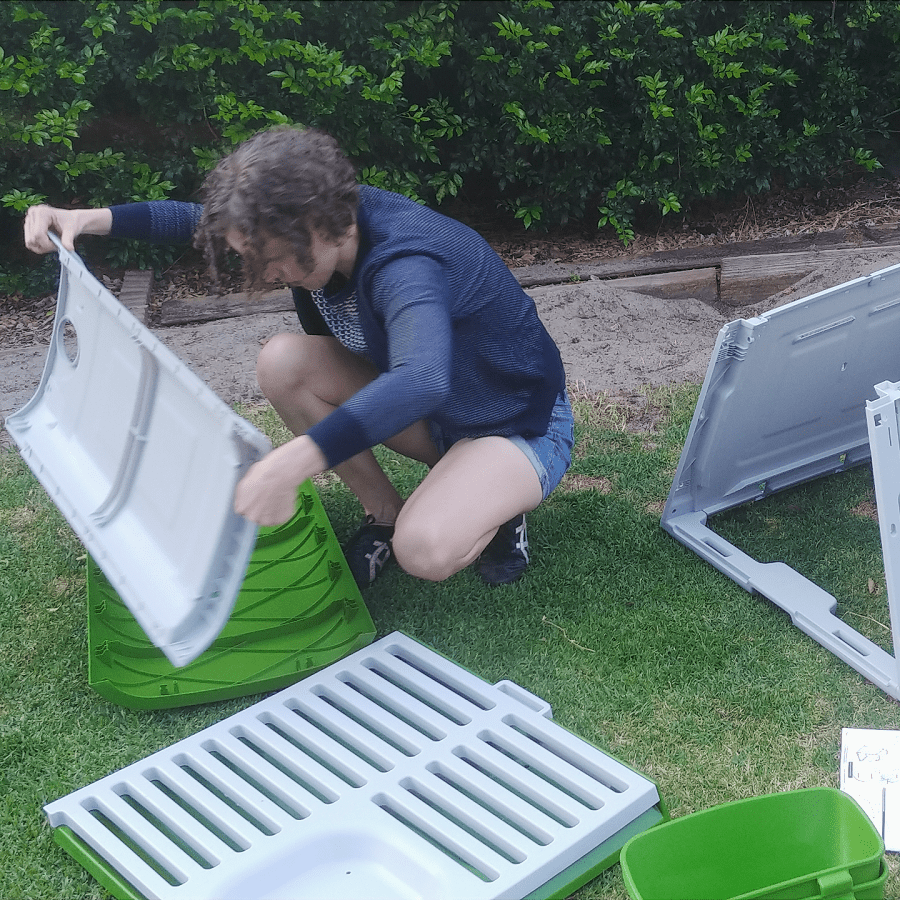

The house comes as two sides, a base, a roof, a back and a front – and some green external cladding (they also have a pink option) that insulates the coop.

Screwing it together was relatively straightforward.

Once the house is screwed together (but before the outer green cladding goes on) the stand needs assembling – the frame that the house sits on.

There is also the option to add wheels to this frame, to make the coop easier to move around the garden. You hold the opposite end and maneuver the coop into the position you want. If you’re intending to keep the coop in the same place, you probably don’t need the wheels. You can also lift the coop with two people as an alternative.

Once the frame is assembled and the wheels attached, the house sits on top and is held in place by two sturdy metal holding plates. The green cladding clips in place, and the house is done.

Wondering how the chickens get into their house? With a ladder, of course!

Next, assembling the run.

Setting up the Omlet Eglu Go Coop Run

Predicted set-up time 2 hours, actual set-up time 2 hours.

No tools at all required for this bit.

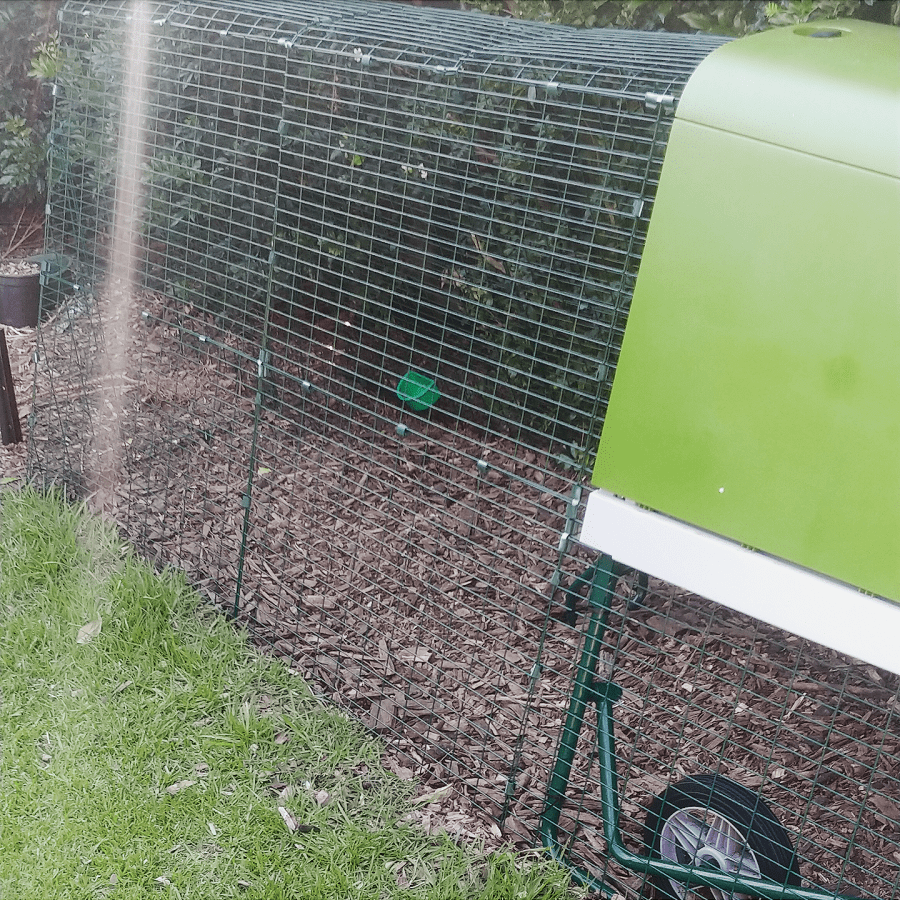

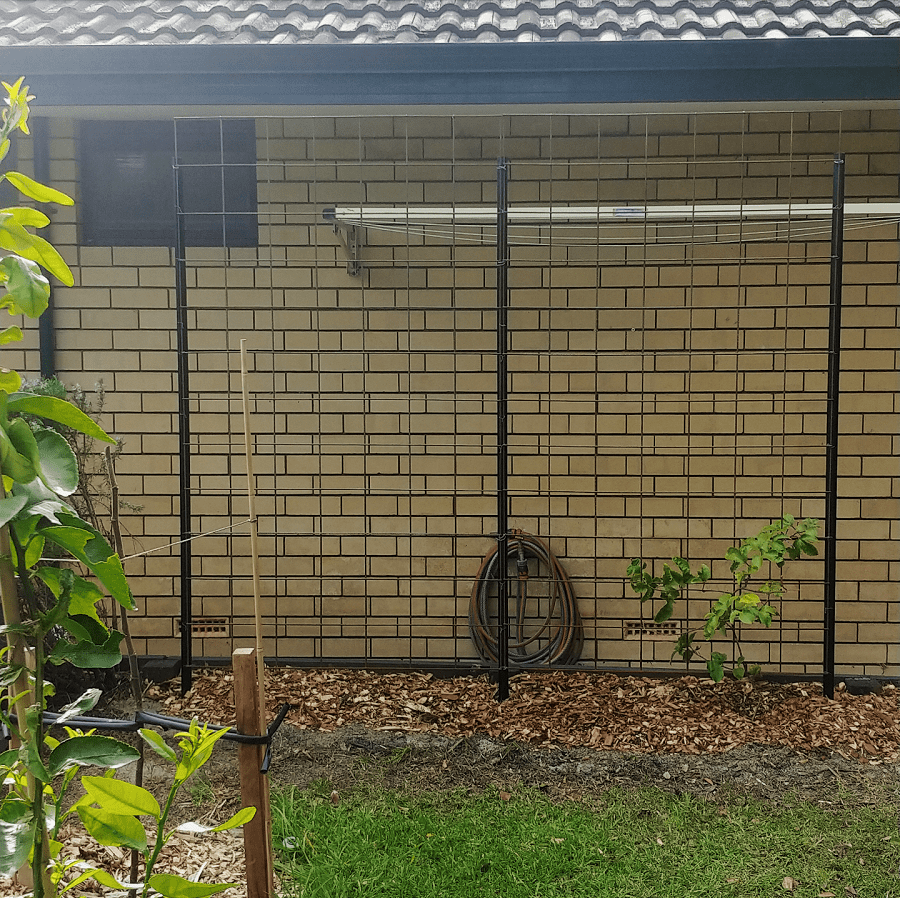

The run is made up of a series of welded mesh steel panels that securely attached to the coop. There’s also a mesh ‘skirt’ that can go around the edge to help deter predators (I haven’t used the skirt as I’m fortunate enough to live in an area without foxes).

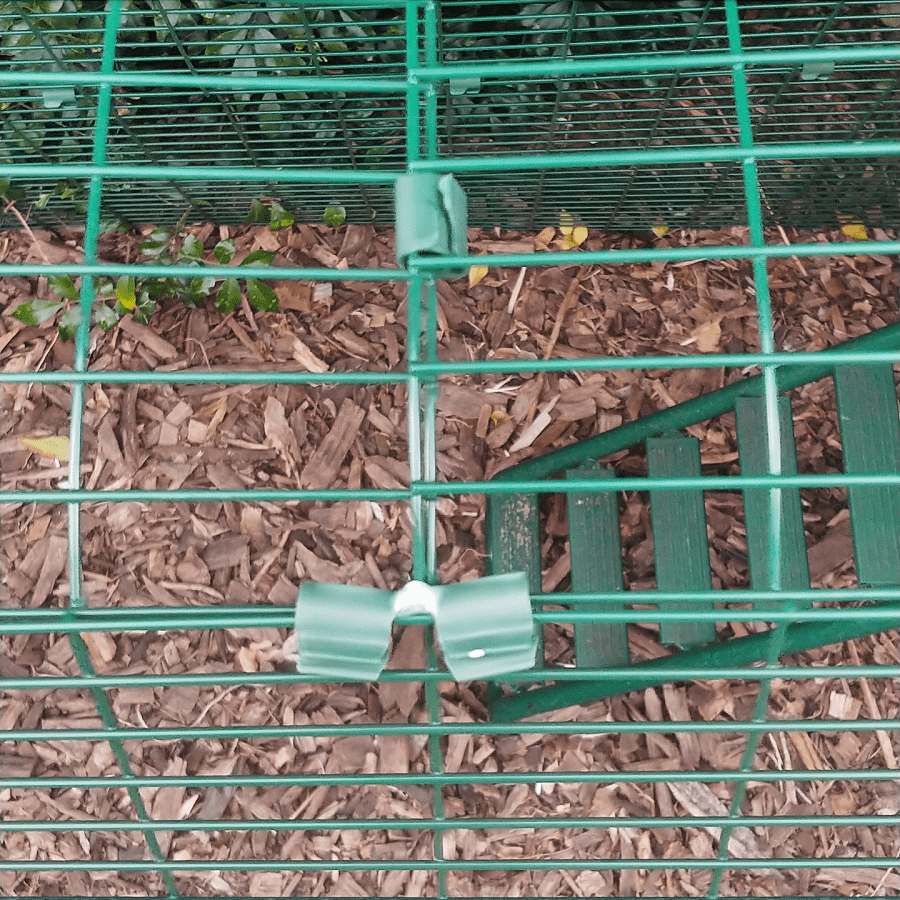

The mesh panels clip together with plastic clips. That might not sound super secure and it’s a little wobbly whilst it’s being put together, but once it’s all in place it’s pretty sturdy.

The clips can be opened and closed to allow for the run to be dismantled. Being plastic, I am sure the bending of the joint will slowly weaken over time, and also degrade in (Australian) sunlight. A follower on Instagram told me that after 4 years in the Queensland sun her Omlet coop clips have started to break. Replacement clips are available, or you could use wire, string, or something else to secure it all in place.

It’s helpful to have two people to assemble this – one to hold the pieces in place whilst the other clips them together.

The coop can be purchased by itself, or with a 2m run, and any number of 1m extensions can be added. I added a single extension to make my run 3m. The longer it is, the more awkward it would be to manuevre the coop/run around the garden, but 3m is fine.

A quick tour of the Omlet Eglu Go UP chicken coop

The door to the chicken coop can be swung open and shut with a liftable and turnable knob placed in the roof.

The side panels have vents, so closing the door does not affect air flow, but it helps keep the chickens secure – a great feature if predators such as foxes or snakes are a concern.

At the back of the chicken house there is a removable panel which can be taken off by turning the big knob at the back, and this gives access to the coop.

The internal tray is removable and slides out, and is made of two parts (the top one is grey, and the bottom on is green). On the top part there is a nesting box area, set slightly lower than the rungs, and then the rungs. (Chickens prefer to perch on flat or wide beams, so these work well.)

There are gaps between the rungs so their poop drops into the bottom tray. The two trays separate easily, and the whole thing can be hosed down to clean.

Honestly, cleaning this coop is a dream.

And of course, to test it out… I have two new chickens.

These two have come from friends who are travelling around Australia for a year. The orange feathered chicken – a solid Isa brown called Dorothy – was too busy eating to pose for pictures. The grey chicken, Betty, is the sister of Alison, my existing Araucana chicken.

Oh and fun fact – araucana chickens lay blue eggs!

Final thoughts on the Omlet Eglu Go UP

I’m really impressed with this mobile chicken coop. It’s well designed, sturdy and secure. The coop is completely weatherproof, and easy to clean. (I can’t stress enough how easy to clean it is.) And whilst I expect some colour fading in the sun, it’s robust and made to last (the house is UV stabilised, and the run is metal), and a zero maintenance option.

If you have zero or minimal DIY skills, it is a great no fuss option.

I love the fact that it’s adaptable (by placing on the ground and removing the perch tray, it becomes suitable for quail or rabbits) and modular, and that the company sells spare parts.

There’s also a thriving second-hand market for these items so if you no longer need it down the track, it’s easy to find a new owner. (That said, it’s less easy to find Omlet products second-hand, as they get snapped up quickly and are often priced similarly to new products.)

You’ll find more information about the Eglu Go UP (and all the other pet products that Omlet make) on their official websites (and don’t forget, if you choose to make a purchase you can save 10% with the code TREADING10)

Omlet Australia / Omlet Ireland / Omlet UK / Omlet USA

And of course, if you have any questions about the Omlet chicken coop – or if you wish to share your own experiences – I’d love to hear from you so please get in touch and leave a comment below!

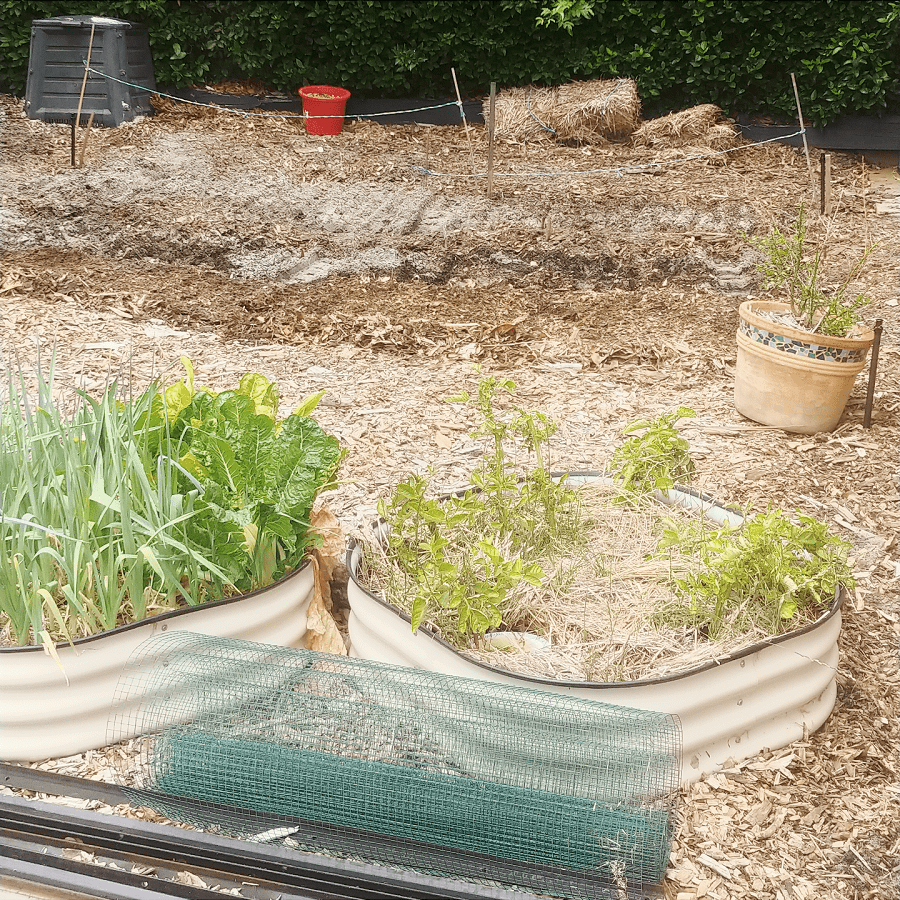

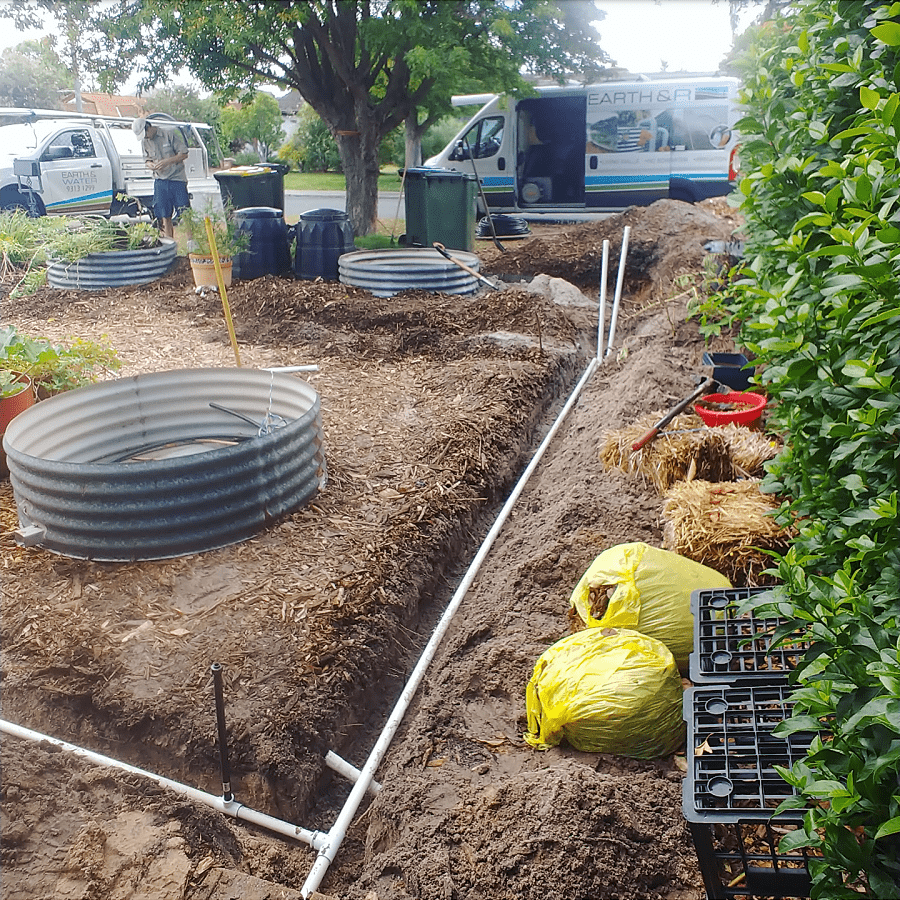

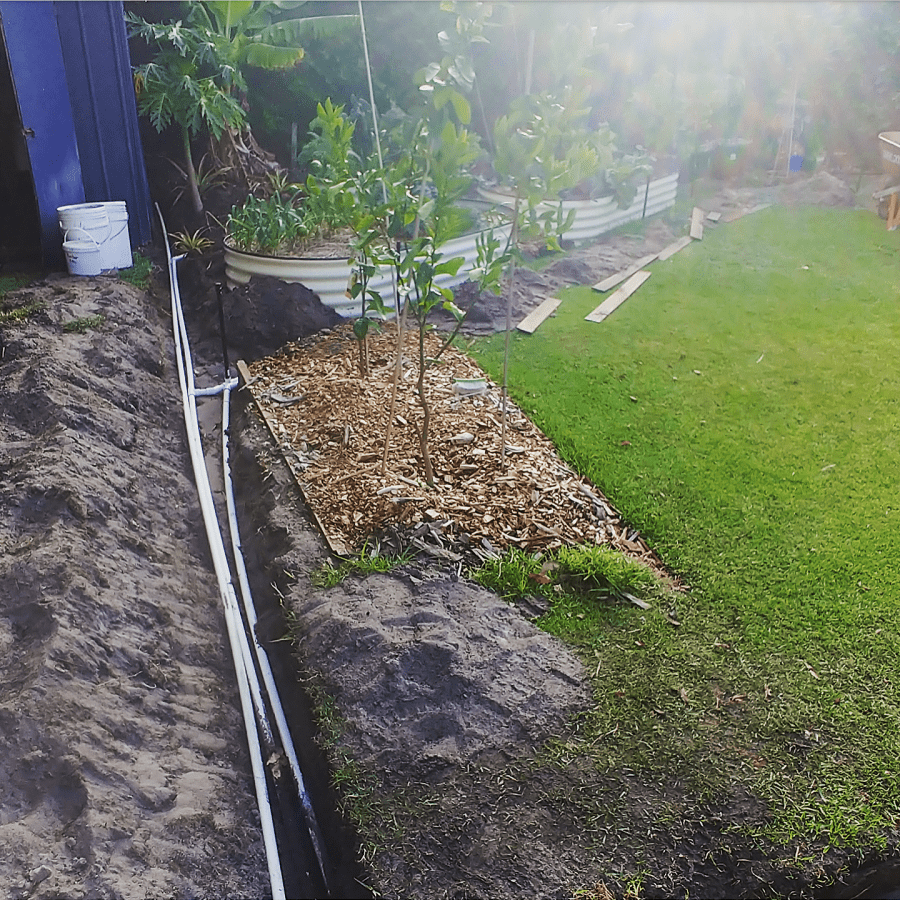

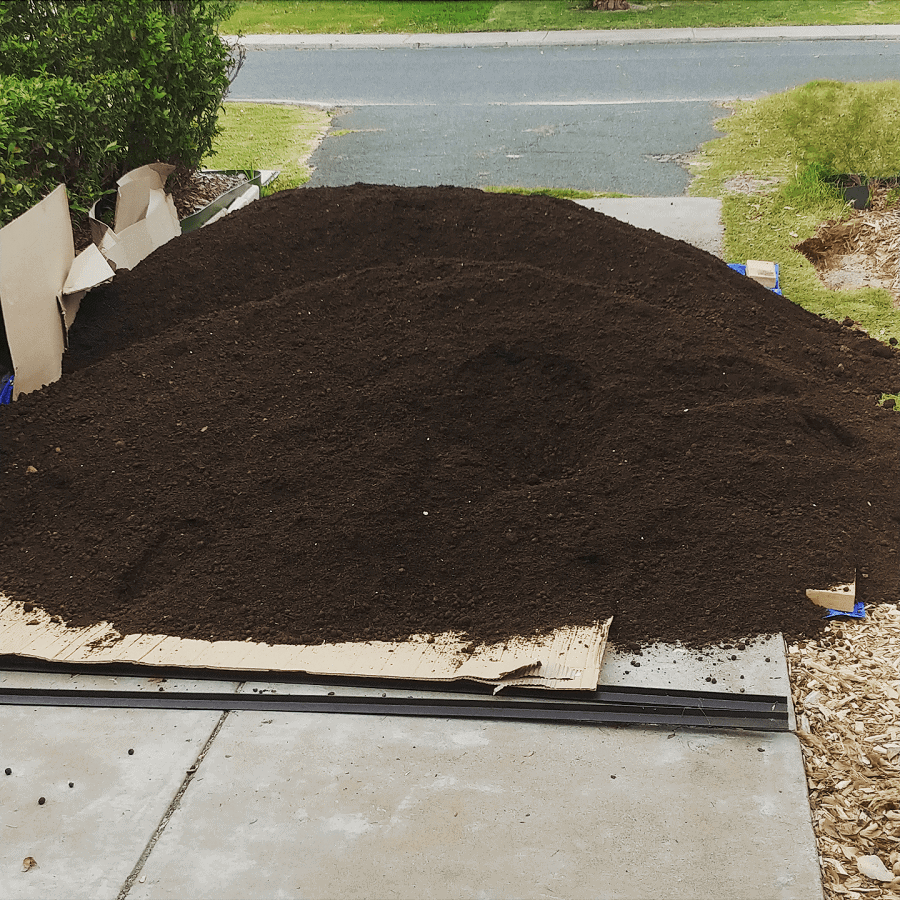

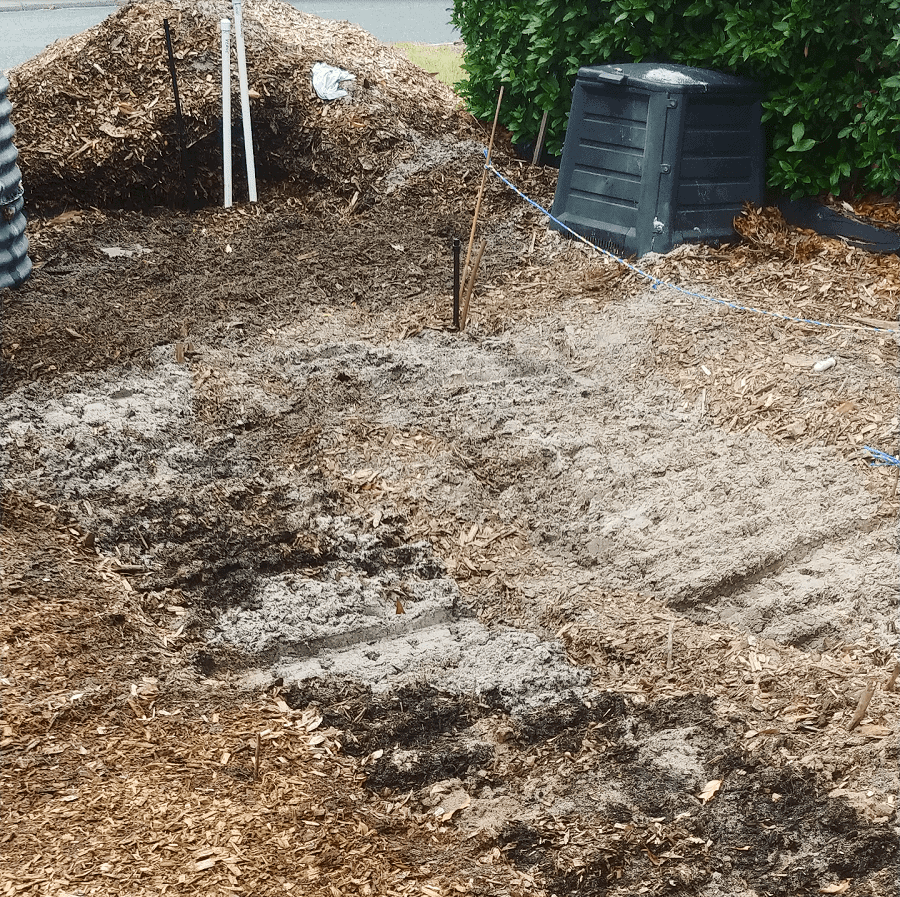

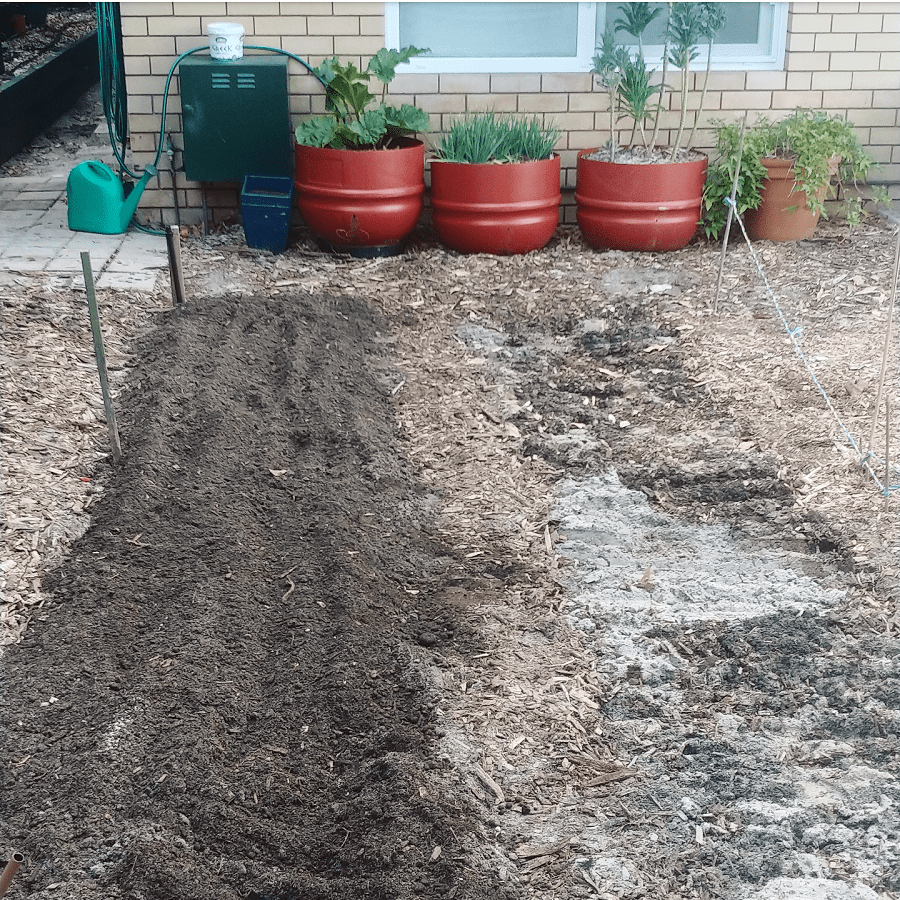

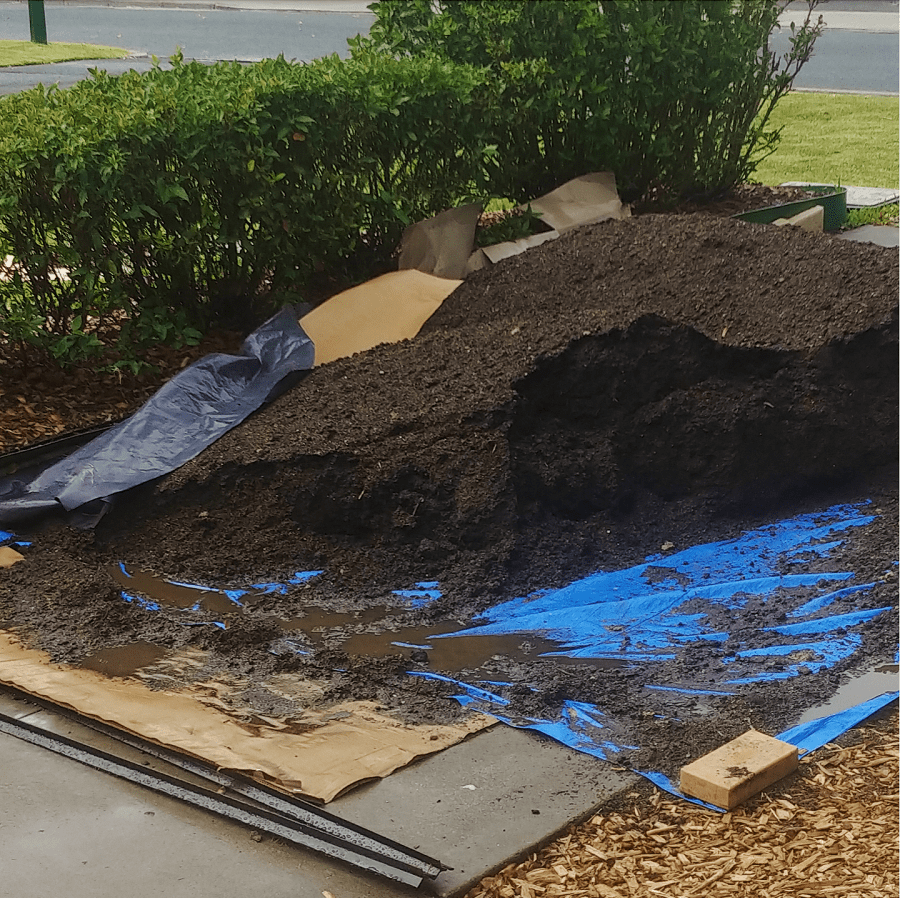

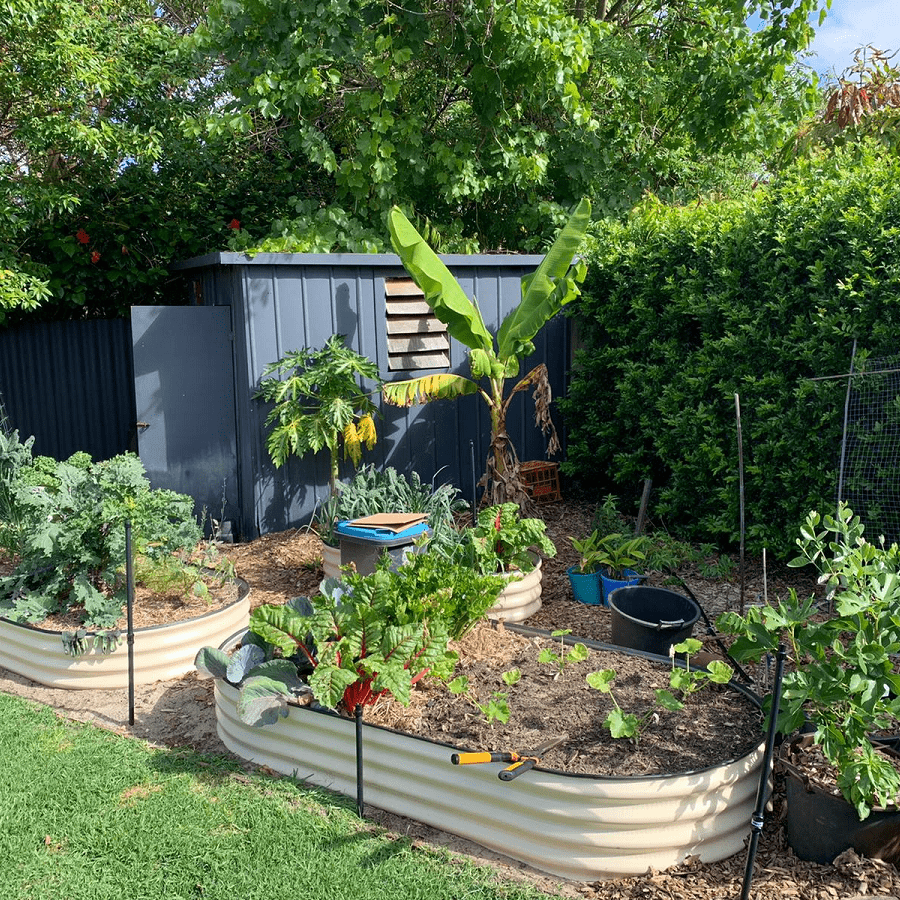

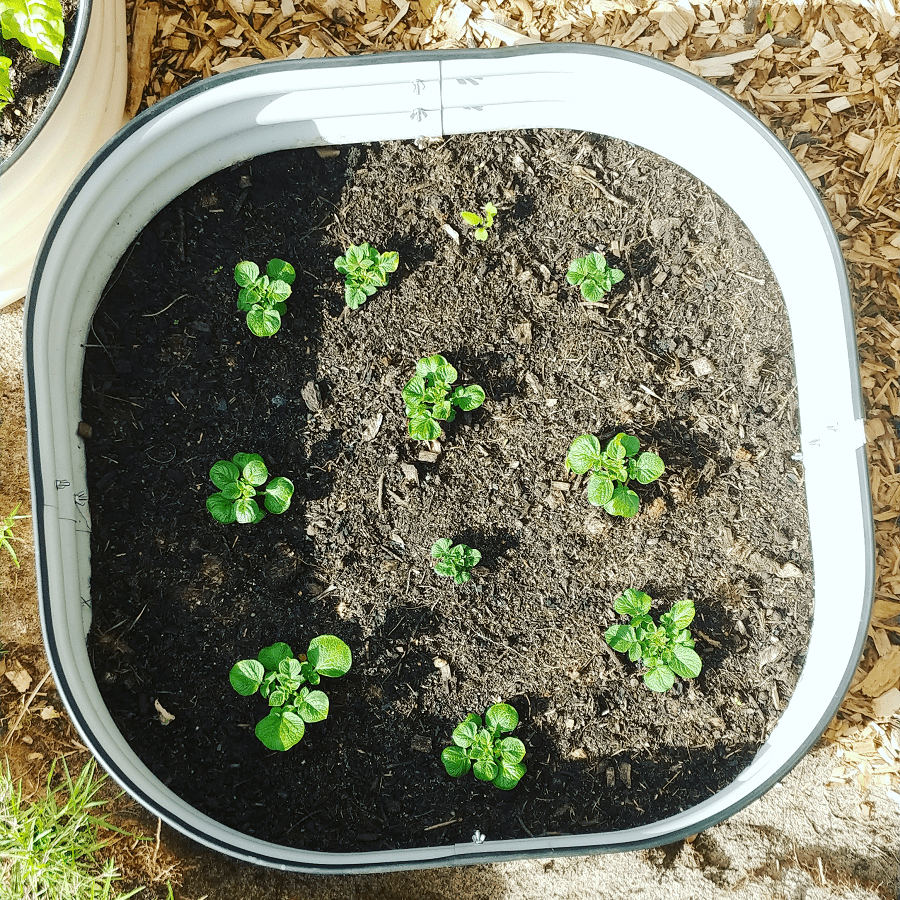

The thing about creating good soil is that you need a lot of compost.

The thing about creating good soil is that you need a lot of compost.