Compostable plastics and bioplastics – and why they aren’t the “green” solution

Bioplastics and compostable plastics are sold to us as a green, sustainable solution. The solution to what, exactly? A solution to the tons of rubbish we send to landfill every year? A reduction in our dependence on fossil fuels? A safe alternative to the hazardous chemicals we add to conventional plastics? Actually, not quite. There’s a lot more controversy to these new plastics than you might think. Did you know that some bioplastics aren’t actually biodegradable, or even recyclable? Did you know that some compostable plastics are actually made from fossil fuels? Did you know that these plastics still require additives to infer specific properties (and to encourage degradation), and these additives may still be toxic?

Confused?

So was I. Fortunately, after a heck of a lot of reading and research, I’m feeling a lot clearer about it all, and hopefully after reading this, you will be too.

First up… Bioplastics

Bioplastics are plastics made from plants. That is all it means. Bioplastics may or may not be biodegradable, may or may not be compostable, and they may or may not be toxic as a result of other chemicals used in their manufacture.

Photo credit: Kingstonist.com via Flickr. Making a difference…what does this statement mean? Is it biodegradable? Compostable? Recyclable? Messages like this are confusing!

The Terms: Biodegradable vs Degradable

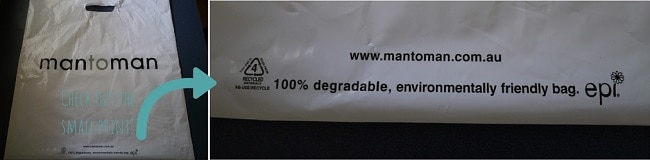

Biodegradable means capable of being broken down by bacteria or other living organisms and returning to compounds found in nature. Degradable means capable of being broken down into smaller pieces. This is not the same as biodegradable. Photodegradable means capable of being broken down into smaller pieces by sunlight. Plastic generally breaks down into microplastics that do not break down further. Most plastics are therefore degradable, but not biodegradable.

Plastic #4 (LDPE or low density polyethylene) is made from fossil fuels; it is not biodegradable, it is not compostable and it is not commonly recycled. Yes, it will degrade over time into thousands of micro pieces of plastic. How is that environmentally-friendly? Beware of greenwashing!

More Terms: Compostable vs Biodegradable

Compostable means capable of breaking down in a compost pile. Compostable plastic [as defined by the plastics industry] is “that which is capable of undergoing biological decomposition in a compost site such that the material is not visually distinguishable and breaks down into carbon dioxide, water, inorganic compounds and biomass at a rate consistent with known compostable materials”. ‘Carbon dioxide, water, inorganic compounds and biomass’ technically includes every substance in the known universe and this definition allows compostable plastic to leave toxic residues whilst still being classified as compostable.

A plastic may be biodegradable but not compostable, meaning it will break down more slowly than would be expected in a compost pile, and may not disintegrate.

Commercial Composting vs Home Composting

Compostable bioplastics may require industrial composting facilities to break down. This means an active composting phase of a minimum of 21 days, with temperatures remaining above 60ºC for at least 7 days, and regular turning. Industrial composting works much faster and better than home composting systems, which generally do not reach the same high temperatures and are not regulated.

It is not always clear with compostable packaging whether an item can be composted at home or whether it needs an industrial composting system, and whether such systems exist. BioPak cups state “compostable and biodegradable” on their packaging, but a quick look at their website finds the disclaimer “BioCup are compostable in a commercial compost facility; however this option is not widely available in Australia”. This means most BioCups used in Australia will end up in landfill, where they won’t break down.

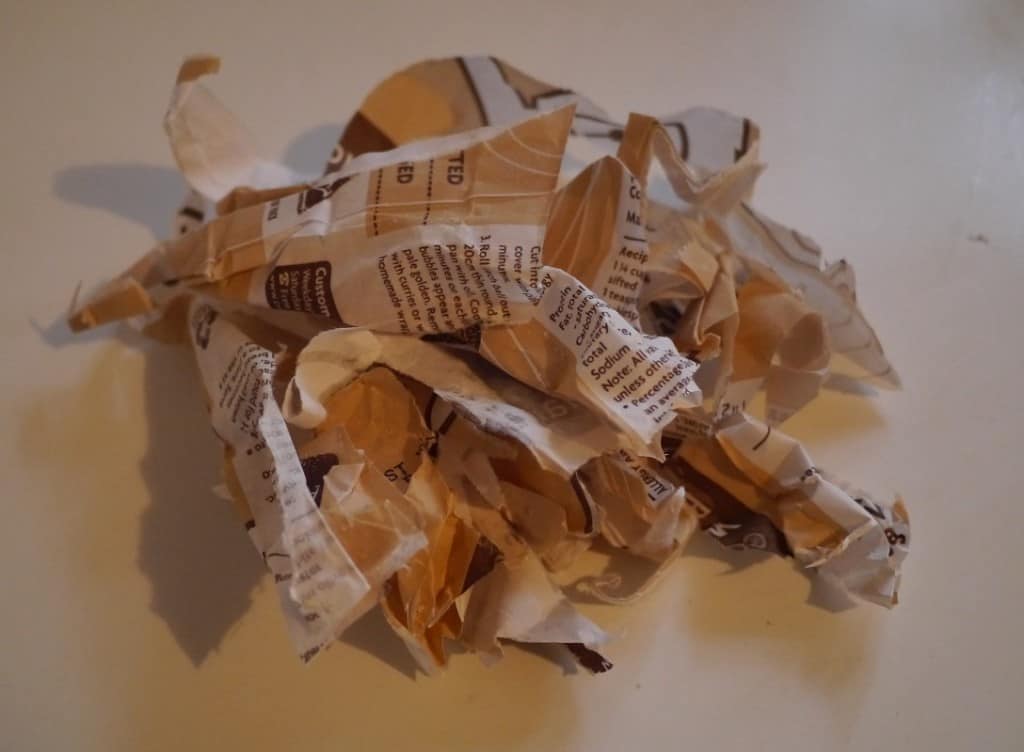

Photo credit: Zane Selvans via Flickr. These Caltech cups are made from corn-based plastic. Caltech don’t compost these themselves (so most will be sent to landfill). To see how compostable they were, Zane put six of the cups in his very active compost pile at home (which reached 70°C a couple of times) and left them for two years. After two years, this is what they looked like.

Biodegradable Plastic

There are two categories of biodegradable plastic, and only one is made from plant materials (bioplastic). The other one is made from petrochemicals (this means fossil fuels).

Oxo-biodegradable plastic is a petroleum-based plastic made from fossil fuels (usually oil and natural gas) with metal salt additives that enables the plastic to degrade when subject to certain environment conditions. This is a two-stage process: following fragmentation, the plastic biodegrades by the action of microorganisms.

Some critics argue that oxo-biodegradable plastics are not actually biodegradable at all, because it is not clear how microorganisms actually break down the microplastics. If polymer residues remain alongside biomass, this would be disintegration rather than biodegradation.

Hydro-biodegradable plastics are plastics made from plant sources such as starch. Hydro-biodegradable plastics tend to degrade and biodegrade somewhat more quickly than oxo-biodegradable ones but the end result is the same – both are converted to carbon dioxide, water and biomass. Hydro-biodegradable plastics can be industrially composted.

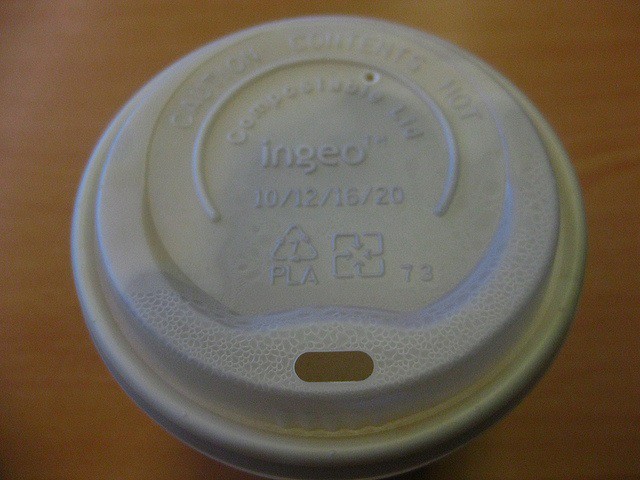

PLA (polylactic acid) is the most commonly used bioplastic (polylactic acid) and costs 20% more than regular plastic. PHA (polyhydroxyalkanoate) is a more temperature resistant bioplastic, and the only bioplastic that will decompose in soil and waterways, but it is more than double the price of regular plastic and less common. PLA will not biodegrade in waterways or the ocean.

What about Recycling?

Oxo-biodegradable plastics cannot be recycled.

The bioplastic PLA can, in theory, be recycled. However, it is grouped under the plastic resin code #7, or “other” along with all other plastics that do not fit into the 6 major plastic types. (Click here to read about the different plastic categories in more detail). This means it needs to be separated from the regular recycling stream which requires technology such as infrared to be sorted correctly. In fact, PLA plastics often contaminate other plastic recycling steams.

Photo credit: Fiona Moore via Flickr. A PLA ‘Ingeo’ bioplastic lid. Plastic type #7 (or ‘other’) is not recyclable.

Additives

As with other plastics, bioplastics still require additives to infer specific properties, and these additives may not be biodegradable, or tested for safety. Natureworks, the largest manufacturer of PLA in the world, state on their website “Although PLA has an excellent balance of physical and rheological properties, many additives have been combined with it to further extend the range of properties achievable and thus optimize the material for specific end use applications.” For bottles made with their PLA ‘Ingeo’ plastic, Natureworks suggest these “basic” additives are used:

- Toner and colourant: without additives ‘Ingeo’ is slightly yellow, and adding a toner can make the plastic colourless and more appealing to customers. Alternatively they may be used to make the plastic a different colour.

- A reheat additive can be used to make the heating process more efficient whilst molding the bottles.

- A UV Blocker will be required if the product is sensitive to UV light, or in order to prolong shelf life.

- Oxygen absorbers can be added to protect products sensitive to oxygen.

- A slip or process aid can be added to help prevent bottles scuffing and scratching during manufacture, packing and transport.

Anything else?

Manufacturing bioplastics is a complicated and energy-intensive process, and still depends on fossil fuels. In addition to the manufacturing processes themselves, energy is required to power farm machinery needed to sow and harvest crops used as the raw materials, and also for transportation. Fossil fuels are also used to make fertilisers and pesticides to used to increase crop yields.

Another question often raised is whether it is appropriate to use vast areas of land suitable for agriculture to grow crops to make plastic rather than for food production.

What about genetically modified food? NatureWorks, the largest PLA producer in the world, is an American company that uses corn to manufacture bioplastic. 30% of all corn grown in the USA is genetically modified, meaning GM corn is used in the manufacture of NatureWorks bioplastic. Whilst the final products are chemically altered and free from GM products, these bioplastics are still supporting the GM industry.

The Verdict?

Whether we’re talking conventional plastics or bioplastics, there’s nothing green or sustainable about using these materials for a matter of minutes and then throwing it away. Whilst bioplastics may have the potential to be composted and decrease the landfill burden, their manufacture and transportation is still hugely dependent on fossil fuels, and they still contain undeclared additives that may leach into our food, or our soils. The reality is that most of these bioplastics don’t end up in composting facilities, but head to straight to landfill, or worse, end up as litter.

If you truly want to be sustainable, don’t use plastic, and don’t use bioplastics either, especially for single-use disposable items. Simply bring your own.

[leadpages_leadbox leadbox_id=1429a0746639c5] [/leadpages_leadbox]

I should probably add that my zero waste week does not extend to toilet paper. I’m still using regular toilet paper in all its single-use disposable glory! Even if it isn’t being sent to landfill, technically it’s waste as it’s going into the toilet, but reusable cloths are not happening in this house any time soon. Even if I was up for it (and I’m not), there is no way I’d convince my boyfriend!

I should probably add that my zero waste week does not extend to toilet paper. I’m still using regular toilet paper in all its single-use disposable glory! Even if it isn’t being sent to landfill, technically it’s waste as it’s going into the toilet, but reusable cloths are not happening in this house any time soon. Even if I was up for it (and I’m not), there is no way I’d convince my boyfriend!