Community Composting (+ Tips For Better Compost)

One of my favourite things about living with less waste is that there is never a single solution. There are always lots of solutions. Different options work better for different people and different situations, but there will always be a way.

In Australia, 40% of our landfill bins consist of food waste. Trimmed off bits, peels, skins, seeds, cores, outer leaves, shells, things we left in the fridge a little too long, bad bits, leftovers.

We toss this stuff in the general waste bin, and off it heads to landfill. Which, contrary to what many people believe, isn’t a giant compost heap. It’s a tomb of waste, sealed by layers of rocks (or sometimes layers of plastic) in between the layers of rubbish, and slowly releasing methane into the environment.

At the same time as we throw our food scraps in the bin, we head to the garden centre to buy plastic bags of compost to help our plants grow better.

We’ve got it all wrong!

So what can we do with our food scraps instead?

Before I moved to Australia, I lived in Bristol (in the UK), and I was fortunate enough to have my organic waste collected by the council every week and taken to an industrial composter. This isn’t an option where I live now (although some councils are currently trialing it).

Even if it was, I wouldn’t use that service now. I would rather keep my food waste (it is a valuable resource!) and turn it into something I can use – or donate it to someone else who can use it instead.

I’ve talked about some different ways of dealing with food waste before: DIY worm farms, done-for-you worm farms and bokashi bins. If you’re just starting out on the living-with-less-waste journey, setting up systems at home can take a bit of time.

As always, there’s a solution. Community composting!

For anyone wanting an easy beginner’s solution, or for anyone without the time or space to set up their own systems, community composting banks are perfect.

What Is A Community Composting Bank?

A community composting bank is simply a location where members of the community can go to deposit their food scraps.

(They are not necessarily called “banks”. I was thinking about this word, and whether it was better to use the word “hub”, “centre” or “facility”. A phrase popped into my head that I’ve heard many times before: “growing your own food is like printing your own money”. If compost is what helps us to grow food, then I think bank is the best word after all.)

The best composting banks are those with capacity to handle the scraps they receive; those with unrestricted access; and those that are managed/overseen by someone to check they are working properly, not contaminated or full of pests.

By “best”, I really mean “easiest to use”. That’s not to say others don’t work well too. Given the choice, I’d prefer to turn out to a facility that is open/accessible, has space to take my scraps, and isn’t infected with cockroaches.

I’d still come back if I turned up to find the place was locked, or the bins were full, but not everyone will. To reach the maximum number of people, things need to be as easy as possible.

The other important consideration is location. A 24 hour access composting hub on the other side of town is less practical than the restricted access compost bins just down the road.

As with most community initiatives, the more local, the more useful and likely to be used.

How We Set Up Our Community Composting Bank

I run a community composting hub together with my friend and neighbour. Originally, both of us listed our home compost bins on the awesome website sharewaste.com, a free-to-use service connecting people with food scraps with people with compost bins.

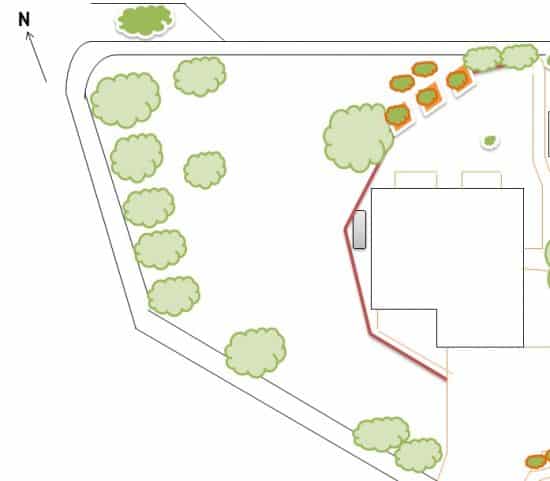

Around the same time, we started a Food Tree project on the land next to my house, planting 34 food trees for our community. We realised that these trees are going to need a fair bit of compost.

We had space for compost bins and we knew plenty of people in our community would be eager to donate their food scraps to our bins.

We started with two bins, and have now increased to five (all donated or sourced second-hand).

As people contact us via Sharewaste, we ask them to bring their food scraps here, and started making compost.

Managing A Community Composting Hub

As with everything, the more people who get involved with something, the more likely it is that things will go awry. With about 20 families currently emptying their food scraps into our bins, we started noticing more and more that things weren’t quite as they should be.

I should add that this is not the fault of the people donating their scraps. As the managers, it is our responsibility to make sure it is all working.

If people haven’t had compost bins before, there is no reason why they would know what is good and what is not.

There were a few problems that we had in particular.

Fresh food scraps going in whichever bin.

This meant all five bins would have fresh food scraps mixed into varying degrees of compost – frustrating when we wanted to dig out the ready compost and there’s a bunch of veggies in there too.

We realised that whilst it might be totally obvious to us which bin was the one for new food scraps, it certainly wasn’t clear to everyone!

Too many veggies scraps (too much nitrogen).

Compost bins need a balance of nitrogen and carbon. Nitrogen-rich scraps are anything green and fresh; carbon scraps are anything brown or dead. Veggie scraps are high in nitrogen. If the only thing being added is fresh green nitrogen-rich scraps, the bin will get stinky and attract flies and other pests pretty quickly.

For all of the green scraps added, some browns (carbon) need to be added too.

Food scraps not being mixed in.

A big mound of fresh veggies sitting on top of the compost pile will not break down nearly as well as those food scraps stirred in, because that is where the microbes are – inside, not on top! Not to mention that food on top will attract pests.

Too much carbon.

Less of an issue as most people are donating food scraps (nitrogen), but we did find one compost bin completely filled with shredded paper – and nothing else. Without anything else, that would have sat there probably for years, breaking down ever so slowly. In the same way as there can’t be too much green, there definitely can’t be too much brown.

Setting Up a Composting System That Works

My neighbour and I talked about all the issues, and how to reduce them in future. Community things need to be easy, and we felt a big list of rules would be overwhelming and put people off – which is the last thing we want!

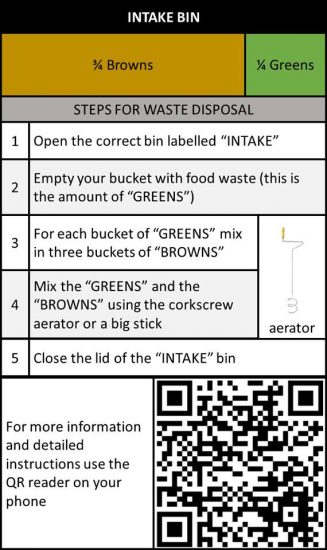

We worked through the issues one by one, and have implemented a system.

Firstly, we decided that it was too difficult to expect people to figure out which bin was the one to add their scraps to simply by looking.

We decided instead to implement a linear system, where the scraps always go into one designated bin, and then we will move into other bins along the line manually.

(This means we can also check there’s nothing strange being added.)

We also decided that to make it easy for people to add carbon to their food scraps, we’d set up a bin solely with carbon so they could simply scoop some in afterwards.

Then, we added some signage and labels.

We wrote up the basics on a sign, weatherproofed it and secured it to a post.

We wrote a document with more tips and tricks (the stuff that we’d like people to know) and added a QR code to the sign, so if they have a question, they can check.

We’ve also secured the aerator/composting fork to the signpost (and explained in the sign what it is for) so that it is easy for people to mix their food scraps into the existing compost.

We painted labels on the two bins that people need to use. When in doubt, always label.

In short, we’ve tried to predict in advance what could go wrong, and then solve it before it happens. So far, it seems to be working well.

Looking for a Community Composting Hub?

If you’re feeling inspired to hook into an existing hub or maybe start your own, my first suggestion would be see who else is in your area via sharewaste.com. My second suggestion would be to contact your nearest community garden.

If both of these fail, consider whether you could set up a mini hub at your place. Even if you only have capacity to take a couple of household’s food scraps, it all helps!

Now I’d love to hear from you! How do you currently deal with your food scraps? Do you like your current system or would you prefer something different? Have you any experiences with community composting hubs – both good and not-so good? Anything other questions? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

[leadpages_leadbox leadbox_id=123a865e9839c5] [/leadpages_leadbox]

The cake is a chocolate pear rosemary cake that’s gluten- and dairy-free. You can find the recipe

The cake is a chocolate pear rosemary cake that’s gluten- and dairy-free. You can find the recipe