How I started a community street planting project

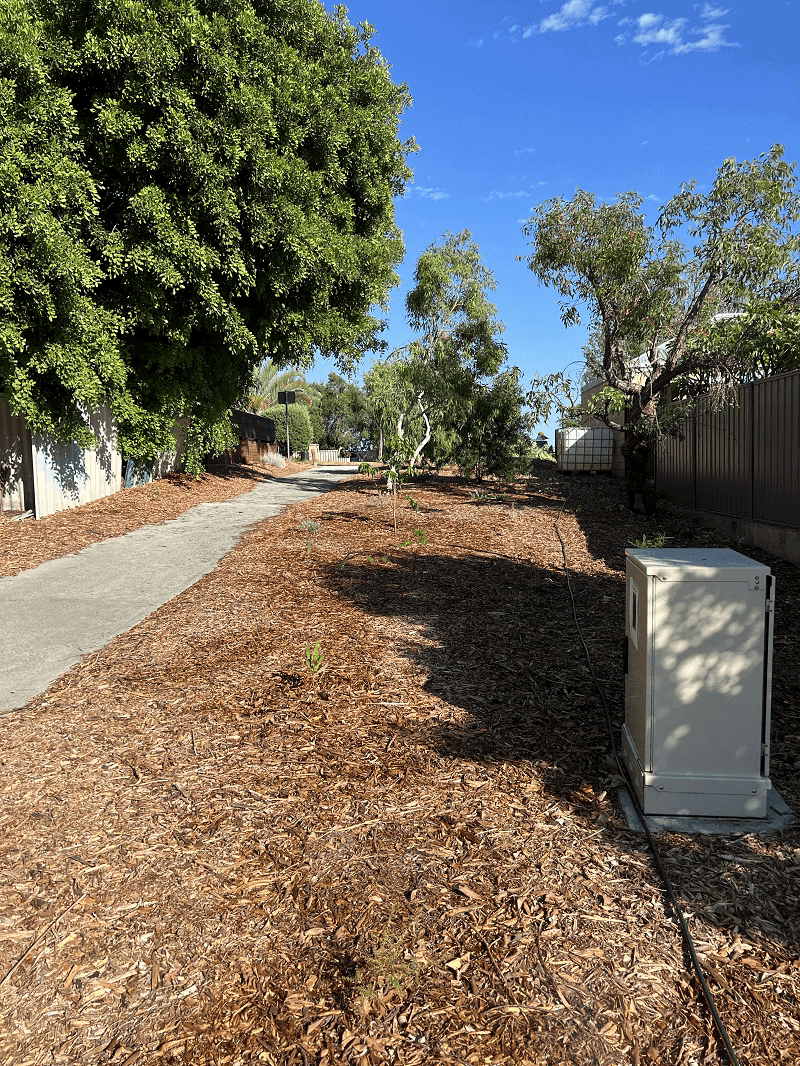

When I moved to the street where I now live two-and-a-half years ago, I immediately noticed the weedy strip of land at the end of it. My street is a cul-de-sac, but at some stage in the past it must have been a through-road to the street behind, because there is still a road-width strip. Now it features a couple of straggly trees, along with a footpath/bicycle path.

The length is about 20m, so it’s not an insignificant size.

Pretty soon after moving in, I hatched a plan to clean it up and plant it out.

And now, with the plan in full swing, half the residents of the street involved, the land weeded, mulched, planted out and two-thirds of the tubestock we planted having survived the hottest and driest summer on record, I thought it was time to share.

As well as sharing some progress shots (it will still be a year or so for the truly glorious “after” pics!), I want to do is tell you about the project and the progress and the reasons behind some of the decisions that we made. Hopefully I can tell you about it in a way that will give you some ideas and direction if you’re wanting to tackle a project like this of your own.

Because the more guerilla planting, and making use of neglected urban spaces, the better!

Step 1, create a plan (even if it’s only in your head)

The first step was to figure out what would be the best and most practical way to transform the space.

I’m no stranger to projects like this, and I started a community fruit tree project at my old place, planting out 34 fruit trees on vacant land, which is still thriving even though I’ve moved away and don’t take an active role there any more.

But the two locations are a little different, and so there were different considerations.

One of the biggest limitations in Perth is the climate, in particular the harsh sun and the lack of rainfall all summer.

The reason the fruit trees worked at the other site was that they had access to water via the bore at the strata property next door (with agreement from the strata). So we installed reticulation at that site.

This site doesn’t have this option. There’s one adjacent neighbour and no bore. The current cluster of residents at the this end of the street have been generous with their loan of taps and hoses, but there is no guarantee they won’t move and the new residents won’t be keen.

Established fruit trees need some water, vegetable crops need heaps, but native plants can get by with minimal water, once established.

Water is one of the biggest limitations for garden design in Perth. But it isn’t the only limitation.

- I had no idea how enthused people in the street would be about doing the work, so I wanted something that I knew we could do with a just a couple of people – or even myself.

- I wanted a project that once it was planted out, was low-maintenance. No need to worry about pruning, or pests, or constantly replenishing the soil, or complex watering schedules (all things that need to be considered with fruit tree plantings or veggie gardens).

- I wanted a project that was low cost and with low ongoing fees – maybe replacing a few plants here or there, but nothing more.

So that’s how the plan formed into this: native Australian plants with a few interesting bushtucker plants incorporated.

I toyed with the idea of a couple of olive trees because they are one of the few trees that will survive without to much water once established, but then I thought it would be more fun to keep it native.

And no olives means room for macadamias.

As for funding it, I came up with a brilliant (even if I do say so myself) idea – collect and cash in all the street’s beverage containers eligible for a 10c refund via Cash for Containers.

It also means that people who aren’t interested or physically able to do the gardening part can still contribute.

Step 2, tell everyone about your plan. More than once.

For the first year, whilst I was still forming the plan in my head, all I did was tell everyone in the street about the plan. At every opportunity.

Of course, no-one thought it was a bad idea. Even if they weren’t keen to do the actual work themselves, who is going to complain that you want to transform the weedy patch that gets sprayed twice a year with chemicals into something that is less of an eyesore?

But chewing people’s ears off about the project was a good way to get the idea cemented that it was going to happen, and give people time to warm to the idea of helping.

There were two main questions I was asked.

The first was, “are you going to ask the council?” to which the answer was “no”.

There were a few reasons.

I subscribe to the idea of “ask forgiveness not permission” when it comes to projects like this. Plus I knew the council had a formal Urban Forest Strategy in place. This was exactly the kind of project they were wanting more of.

Having worked with them on the fruit tree project and understanding the steps we needed to take with that, I was fairly confident they’d be happy with this one.

Worst case they could demand we pull the plants we planted out and let the weeds regrow so they could continue to spray them with glyphosate twice a year. This seemed unlikely.

The other sticking point is that it seems that it is not actually council land. Because it was once a road, it’s likely it is road reserve (land kept aside for potential future roads) and owned by the state government, not the council.

(Our last project was also on road reserve.)

Plus, I didn’t really need to ask the council, because I didn’t need anything from them. We had a plan, we had funds for plants, we had labour.

The next question I was asked was, “why don’t we ask the council and see if they will contribute anything?”

I didn’t really see why we needed to do this as we already had everything we needed (and I hate “free” stuff for the sake if it). And I soon realised “why don’t we” meant, “why don’t you” – as in me, Lindsay. And I could not be bothered with more emails.

So I said to a couple of people who raised it, that if they’d like to they were more than welcome to.

No-one ever did.

Step 3, choose an action, set a date, tell everyone about it… and stick to it.

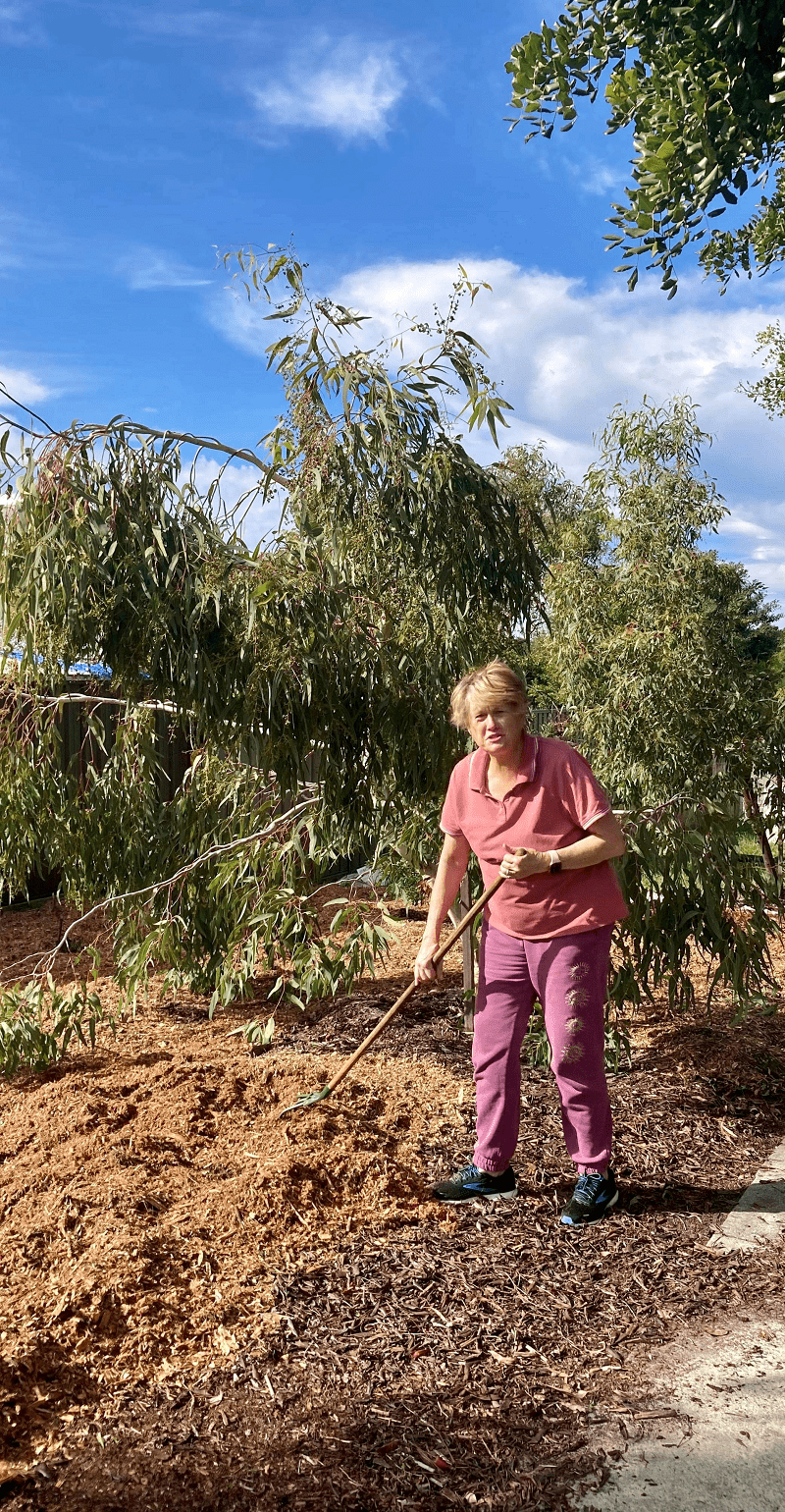

The first action we really needed to do was weed. It’s not everyone’s favourite job, but I quite enjoy it. So I chose a date, told everyone, and then showed up on the day. I was fully prepared to be the only one, but a good handful of neighbours turned out.

Progress had begun.

(I think if you’re the ringleader of a project, it’s important that you chose a date/time that you know you can make, that you turn up first and you stay until the end of the time you said you’d be there until, even if you’re the only one. Turning up yourself is the single best way to get others to turn up next time.)

Step 4, keep momentum going.

As soon as the first action was taken, the second one was arranged, for a couple of weeks time.

We have a street Facebook group which makes it easier to keep everyone updated, share progress pictures and create events.

I ordered some mulch (via mulchnet.com – it’s free but you never know when it’s going to be delivered) and it arrived almost instantly.

And from there, things just snowballed.

We organised a day to finish weeding, and get the weeded areas mulched.

People who couldn’t make the planned days did some weeding and mulching in their free time.

We ran out of mulch! So I ordered a second pile – which came as quickly as the first!

Next it was time to plant.

Our local council gives out free native tubestock once a year to households that register, and a few households on our street signed up, and then donated the plants for our project. Topped up with the natives we purchased with the funds raised from the Containers for Change scheme (we’ve raised over $500 from this!), we had plenty of plants to start the planting.

The initial plan was to plant out one half of the space the first year, but we ended up with enough to plant about two-thirds of the area. (The council, when they found out about our project, donated some leftover tubestock from two of their planting days, which helped fill in some gaps).

Step 5, maintenance (the least fun but most important part)

The fun part is the action – getting everyone together and transforming the space, and planting plants. But maintenance is what keeps it all alive. In summer, the most important thing to do is water. And then water some more.

As the plants get more established, there will be less need for hand watering, but the first summer it’s critical to keep things watered.

As you might expect, there was less enthusiasm for the watering part. If it wasn’t for the next-door neighbours who donated their hose and tap, and ended up doing most of the watering, I think we’d have a much lower success rate with the plants.

(That’s not to say they were the only ones. I marched up there with the watering can plenty of times, and also did hose duty There were others who did their bit too! But we had such a hot and dry summer this year – we are talking record-breaking temps and lack of rain – and they really held the fort with it.)

We have placed an empty IBC container on the space. Originally the plan was to connect to the neighbour’s downpipe, which would have helped in spring but would not have solved the summer watering problem – an IBC container holds 1000 litres, but that wouldn’t have lasted for six months of no rainfall.

The council have now offered to fill the tank with their watering trucks (the ones they use to water the street trees) which will mean it will be much easier to water in future years.

Step 6, plan the next steps

This winter, once the first proper rains start to fall, we will plant out the rest of the area, we will replace the tubestock that didn’t make it, we will order anther truckload of mulch to spread and we will keep on top of the weeding. (In summer there’s no weeds as it’s too dry. But once the rain starts…)

This will be when it really starts to take off, as the plants from last year will come into their own and it will be more plant cover and less woodchip cover.

And you might be wondering how the council are suddenly contributing, when I said at the start that we hadn’t contacted them?

We didn’t need them to start the project. But once the project was underway (and we had something to show them) we invited them to take a look.

And that was when we were offered the excess plants, and later on the agreement to fill the water tank. And they are looking into sourcing a couple of macadamia trees for us!

Of course we welcome their contribution, and are grateful for everything they’ve been able to offer us. But I’m still glad we didn’t speak to them before starting the project. It might have slowed things down. And it’s better that the people of our street feel ownership over the project.

It’s worked out well this way.

It’s now been almost a year since we first began the project. With the winter rains coming the transformation is really going to happen in the next few months.

This year I’m going to do a similar thing with my own verge (plant out with native waterwise species). Maybe it seems strange that I decided to tackle the community project first before my own back (well technically front) yard.

But there’s just something immensely satisfying in getting a group of people together and achieving something collectively as a community.