Reducing Food Waste with Worm Farms: Trialing the Hungry Bin

Zero waste is all about circular living. It’s often talked about in terms of the circular economy (which is the ideal and the one we want to work towards) as opposed to the linear economy (which is the one we have now).

The idea is that materials and resources should cycle, being reused or repurposed or reshaped again and again.

Circular living supports local solutions, which means less packaging, distribution costs and transport emissions; and more connection and resilience within our local communities.

Anything we can do at home, or within our street, or within our suburb, the better.

With this in mind, let’s talk about food waste.

In Australia almost 40% of everything we throw in our landfill bins in food waste. Even more scary, I think, is that 25% of what the average household throws away is food that could have been eaten.

Even if we are super diligent, there’s always going to be food waste that can’t be eaten. Onion peels, lemon skins, cores, seeds, pips, stalks, outer leaves, and general bad bits.

If we want to reduce our environmental impact, processing our food scraps at home is a great solution.

I love it when a problem has multiple solutions, and food waste is exactly that. There’s so many ways we can deal with food scraps at home. No “one size fits all solution” – different methods that work for different locations, spaces and households.

There’s composting (yes, regardless whether or not you have space for your own compost bin), there’s bokashi, and there’s worm farms.

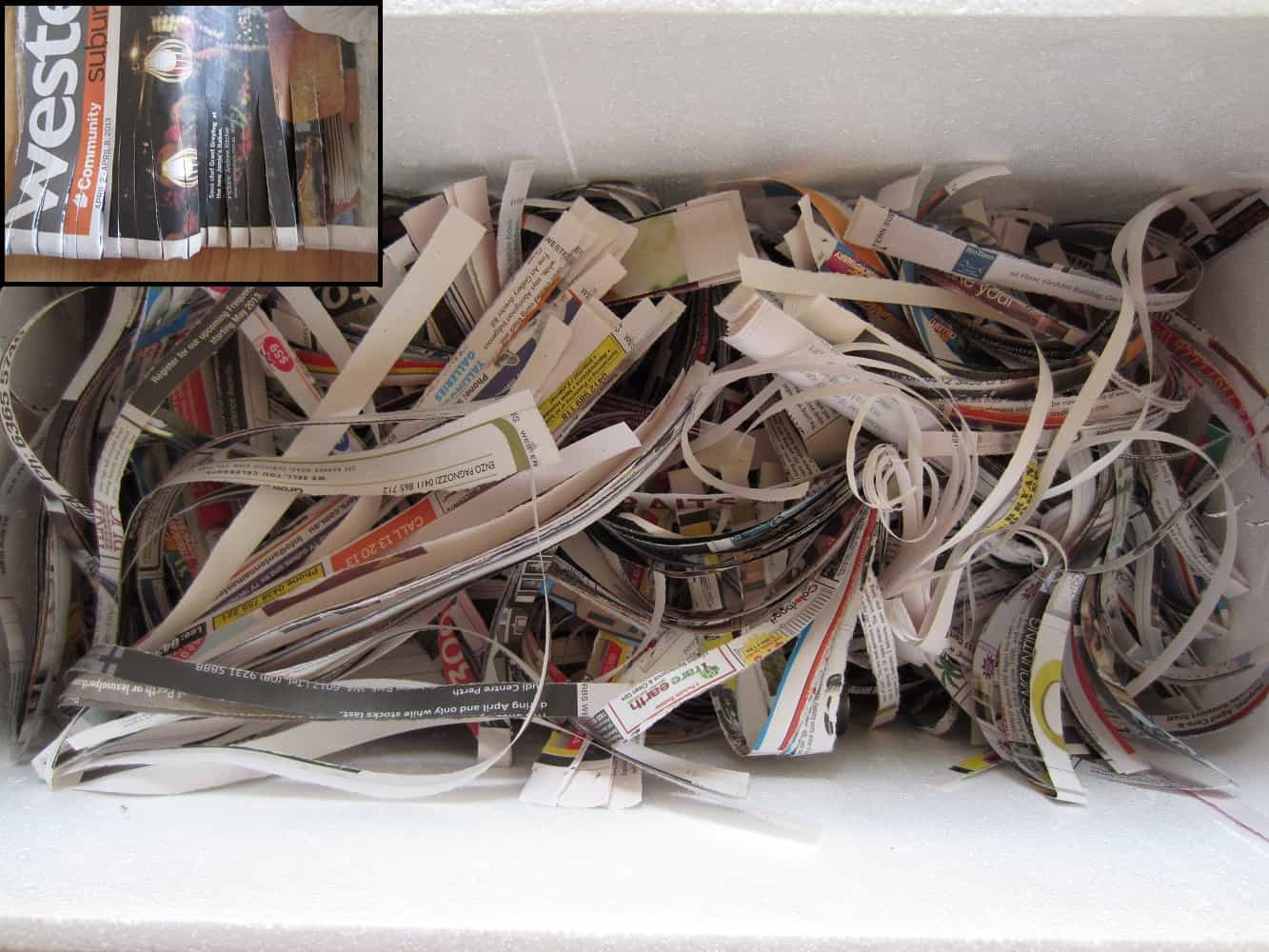

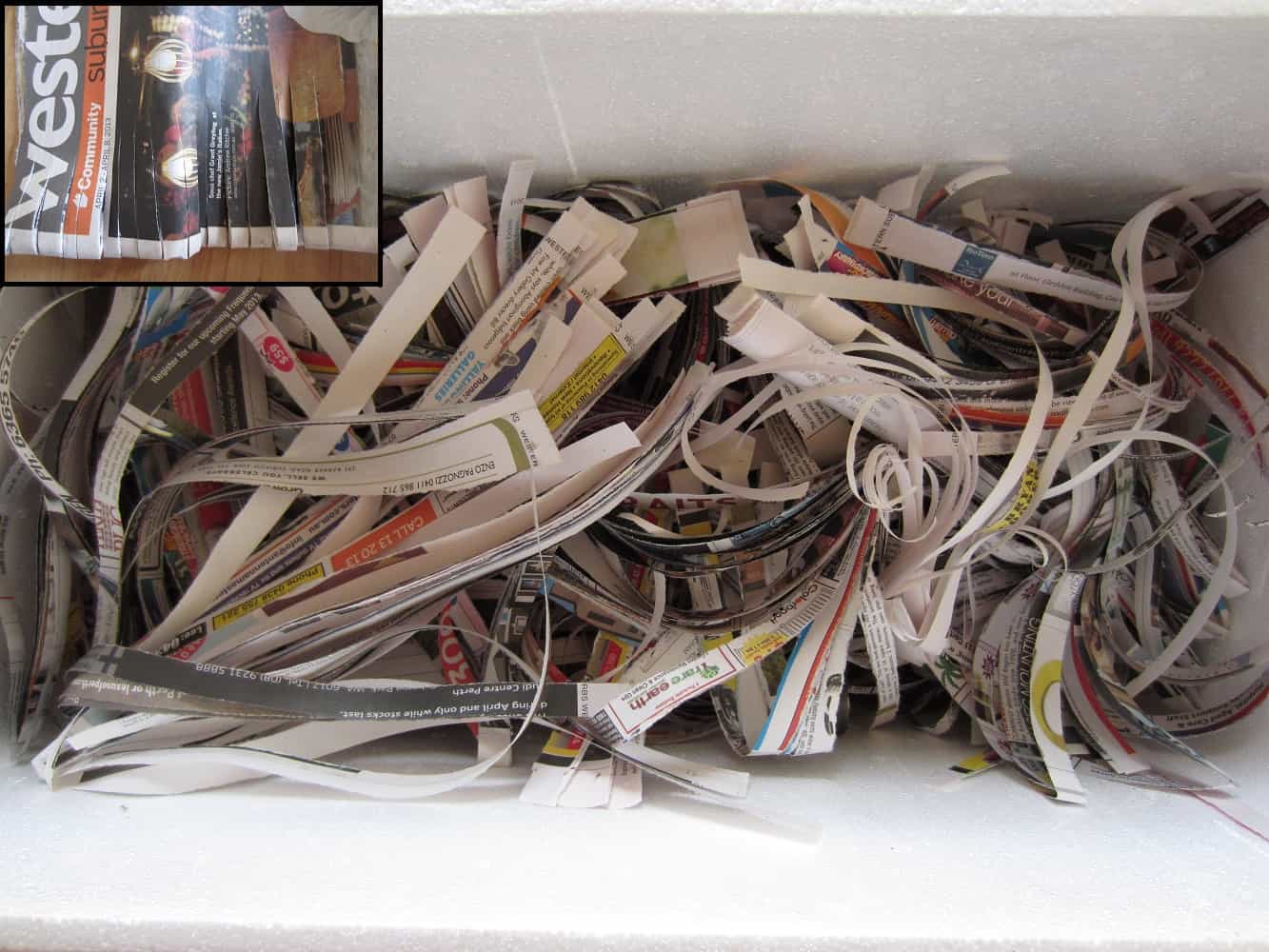

Worm farms were the first thing I tried when I went zero waste, and over the years I’ve successfully used a number of different worm farms: from polystyrene box worm farms that you can DIY yourself, and degassed fridge worm farms (which work like polystyrene box worm farms, but on a bigger scale) to the black plastic worm cafes that can be purchased from hardware stores (or even better, found on the verge).

Over the last three months I’ve been trialing a new design of worm farm: the Hungry Bin, and it’s my favourite so far.

I came across the Hungry Bin worm farm because of my friend Josie (who came across them first). She was so impressed with it as a way to effectively process food scraps for her family of five, that she decided to distribute the Hungry Bins here in Western Australia. She set up her business Pearthworms selling the worms farms last year (in 2017).

Pearthworms were kind enough to loan me a Hungry Bin worm farm to test drive. I’m always keen to learn more about ways for households to reduce their own waste, and love innovative products that make it easier. Wins all round!

Here’s the lowdown.

The Hungry Bin Worm Farm: Composting Food Scraps at Home

At first glance the Hungry Bin might look like a regular flip-top waste bin, but there’s actually a fair bit of thought and engineering that’s gone into the design. It is designed and made in New Zealand.

Firstly, it actually packs down pretty small. The bin is actually made of two parts that lock together, and one fits inside the other, making it a fairly small package. The bin itself is made from UV resistant plastic with recycled content, and is expected to last for 25 years. The packaging is minimal, with a cardboard outer, and none of the parts come packaged in additional plastic.

Once clipped together, the bin is filled with bedding, then food scraps and worms are added to the top. Worms remain near the top, gobbling up the food scraps and creating worm castings, a nutrient-rich medium. More food waste gets added on top, the worms move up to find them, and the castings naturally accumulate underneath.

The tapered design enhances the efficiency of the system. Composting worms are surface feeders, and food scraps are added at the top, so keeping the worms near the surface increases the efficiency. The top is the widest point of the whole bin, and the bin can hold 16,000 worms and process 2kg of food scraps per day.

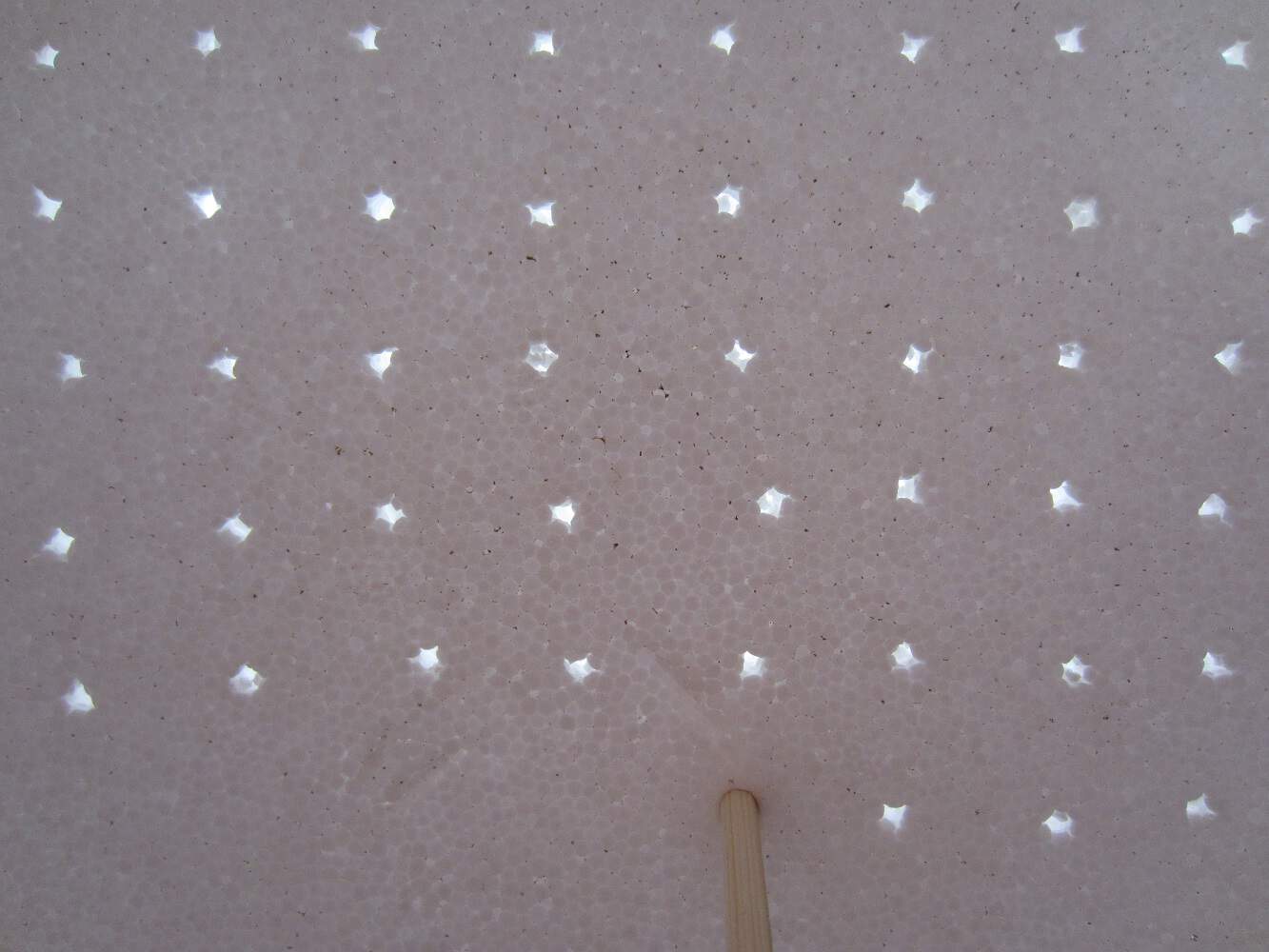

Because the bin tapers, the worm castings naturally compress at the bottom. This encourages the worms to move to the surface and also ensures that when the bottom is removed, the entire contents don’t fall out.

The reason you’d want to remove the bottom is to get your hands on the worm castings. They can be used to grow seedlings, added to pots or to existing plants or dug into the garden. You simply unclip the tray, scoop out the worm castings and reattach.

The bin has a tray that sits underneath, that collects the worm juice. This can be used like a fertiliser.

I trialled mine indoors, but they are intended as much for outdoor use.

Pearthworms and the Hungry Bin

As I mentioned before, I’m a fan of local solutions. Pearthworms is a local, Perth-based business, and they intend to stay that way. They only supply Hungry Bins to people in Perth and Western Australia. With 1.3 million people living in Perth, and probably that same number of cafes and takeaway food outlets (okay, I’m kidding, but there’s a lot), there’s huge potential to make a massive difference without needing to look further afield.

Pearthworms are keen to focus not just on individual households, but also commercial venues: restaurants, cafes (the picture above is Josie with the two bins she has installed at Stackwood Cafe in Fremantle), businesses, community gardens – anywhere that is creating food waste.

Pearthworms also supply happy, healthy worms with the Hungry Bin (Eisenia fetida worms, and 2000 of them, to be exact). It’s easy to imagine these worms would just come in a plastic bag, but no – they come in a natural hessian pouch sewn from an old coffee sack.

Even better, once the worms are added to the Hungry Bin, the sack can be cut in half along the seam to make a cover that perfectly fits the inside of the Hungry Bin. (The cover is important as worms don’t like light.)

My experience with the Hungry Bin in the three months that I’ve had it has been great. It’s dealt with far more food scraps than my other worm farms can manage; it doesn’t smell; it’s so easy to use; it’s much less sensitive to extremes of temperature than other commercial worm farms; and once I get my first tray of castings, my garden is going to love me.

(Plus, this worm farm is going to churn out worm castings for 25 years. That’s an epic deal in the long run, if you think about how many trips to and from the hardware store that would be saving, buying plastic bags of seed raising mix and compost.)

It is a more expensive option (especially when compared to the DIY polystyrene box worm farm approach) but then again, DIY isn’t everyone’s thing. Different systems suit different households, different lifestyles, and different budgets.

The important thing is that we stop sending our food scraps to landfill. How we do it doesn’t really matter. There are plenty of solutions, we just need to find the one that works for us.

If you’d like to chat to Josie in person to find out more or see a Hungry Bin worm farm in action, Pearthworms currently have a stall every Saturday morning at the Subiaco Farmers Markets. Alternatively, their website is pearthworms.com.au.

[leadpages_leadbox leadbox_id=1429a0746639c5] [/leadpages_leadbox]