5 Bad Habits I Shook by Going Zero Waste

Often when we talk about the changes we’ve made since deciding to refuse single-use plastic, reduce our waste and/or live more sustainably, we focus on the products we buy (or no longer buy). There are plenty of articles online about ‘zero waste swaps’ and indeed, I’ve written a few myself.

I thought it might be interesting to change the focus slightly, and rather than talk about products, talk about habits. Now I’ve still got plenty of bad habits to shake (going zero waste does not make you a perfect human, alas), but luckily for me, embracing low waste living has enabled me to shake a few.

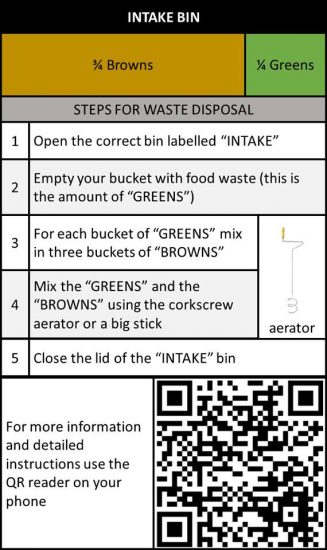

Throwing my food scraps in the trash.

That bin went to landfill, and I just thought that the landfill was a great big compost pile. I found out later it is most definitely not. It’s an engineered (and expensive to construct) depression in the ground that entombs waste without air, and creates a lot of methane instead.

Then there’s the fact that food makes for a stinky bin and attracts flies (particularly in hot climates), and needs hauling to the kerb every few days. Did you know that between 20 – 40% of everything the average householder throws away is food scraps?

Not to mention, I was throwing away my food scraps, and then buying plastic-wrapped bags of compost at the garden centre for my plants!

Setting up a worm farm, and then a compost bin, reduced my rubbish bin to almost nothing, solved the ‘how do I line my bin without plastic?’ problem (if there’s nothing stinky and wet going in the bin, it doesn’t need a liner) and gave me free nutrients for the garden.

There are so many solutions to dealing with food scraps. There are options whether you’ve got a garden, a balcony, or no outside space at all. There are options even if you can’t be bothered setting up and managing a system yourself.

Find more info here: How to compost without a compost bin.

Being ‘in love’ with my recycling bin.

Yep, I used to think that recycling was the best thing ever. (And pretty much that I was the best thing ever for filling it to the brim!) I saw that chasing arrow recycling symbol as my ‘get-out-of-jail-free’ card for packaging. ‘Oh it’s okay. It’s recyclable!’

It simply never occurred to me that I could say no to unnecessary packaging, refuse the excess, reduce what I did use and even rethink some of my choices for less wasteful alternatives.

As I’ve said often, recycling is a great place to start. But when I realised it was not the place to stop, and there was so much more I could be doing, that was when I really began to reduce my waste and my footprint.

Recycling – and learning how to recycle properly rather than chucking everything in and hoping for the best – that’s the first step. But it’s better to have an empty landfill bin and an empty recycling bin than an empty landfill bin and a recycling bin that’s overflowing.

Accepting free samples of everything.

I loved anything that was ‘free’. In fact, if somewhere was offering freebies, I’d quite often take one and then circle back round to take a second one. Because, free!

Cringe.

Whether it was sachets of moisturiser with real gold flakes in them (yes this was a real sample I once accepted), scented foot odour reducing insoles (again, a real thing) or any ‘free’ miniature or travel-sized thing whatsoever from any hotel, I was snaffling these thing up.

The old me thought all this stuff was great. It was duly popped in the cupboard and forgotten about. Yes, most of these freebies I didn’t even use. The new me just shakes her head at the old me.

What about all the resources? The pointlessness? The waste? The perpetuation of the cycle of more samples and free stuff?

Let’s just say, I don’t do that any more. I actually get more satisfaction now from refusing stuff than I ever did from taking it. (The only freebies I get excited about these days are my friends’ excess garden produce and cuttings from their plants which I’d like to grow in my garden.)

Taking ‘eco-friendly’ labels at face value.

Even before I went plastic-free and low waste, I’d buy all of the eco-friendly products. It was pretty easy, because so many products are labelled ‘eco-friendly’!

(Or if not ‘eco-friendly’, the equally eco-friendly sounding ‘green’. Bonus points – in my mind – for having an image of a green leaf on the packaging.)

It was only after I began to reduce my waste that I began to question these labels, and stopped taking them at face value.

There are no independently verified certification scheme for labels like ‘eco-friendly’ or ‘green’. (Or ‘biodegradable’ for that matter, but I won’t go into that now. If you want to read more, you’ll find my post ‘is biodegradable plastic: is it really eco-friendly‘ a helpful read.)

Anyone can write labels like ‘eco-friendly’ and ‘green’ on their packaging. And they do!

Rather than let the person who designed the packaging tell me that a product is eco-friendly, I now prefer to do my own research. If a company is truly environmentally responsible, committed to sustainability and equitable in the way they do business, they will be able to back up their claims.

They will be transparent, happy to answer questions, eager to find out answers that they don’t already have, and keen to talk more!

If ever I write to a company claiming to be eco-friendly, and receive responses that are cagey, defensive or hostile, I choose not to support those companies.

That’s not to say I can always find all the answers. But I make an effort and try to be conscious in my choices.

Waiting for ‘somebody else to do something about that.’

Before I decided to reduce my single-use and other plastic, I was the person picking all the overpackaged things off the supermarket shelves and muttering how ridiculous it was, and how somebody should do something about that, whilst piling those same things into my trolley.

I thought it was up to the manufacturers to change their packaging. I thought it was up to the stores not to sell these items. It did not cross my mind that I also had a role to play in this, and a way to influence change – I could just not buy them.

I don’t think it is solely the responsibility of individuals to create change. But we buy things and support (or don’t support) brands and companies, and companies pay attention. We can apply pressure, start conversations, write letters, share the good and try to hold the bad to account.

I don’t have the empirical evidence, but I’m pretty sure that nobody ever successfully influenced change by muttering under their breath. Nor by doing the exact thing they were complaining about.

It feels so much better to be doing something, and trying, however small that ‘something’ might be.

Embracing a life with less waste might not have ironed out all my flaws, but it’s definitely helped me shake some bad habits along the way.

Now I’d love to hear from you! What bad habits (if any) have you kicked through reducing your rubbish and trying to live more sustainably? Any bad habits you’re trying to shake that are still a work-in-progress? Anything else you’d like to add? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!