Biodegradable Plastic: Is It REALLY Eco-Friendly?

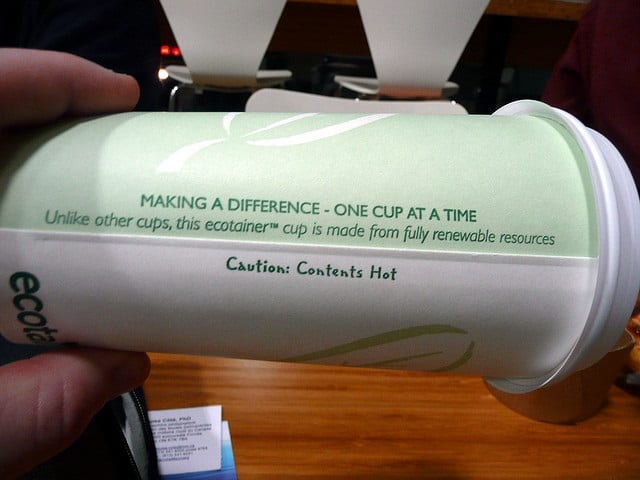

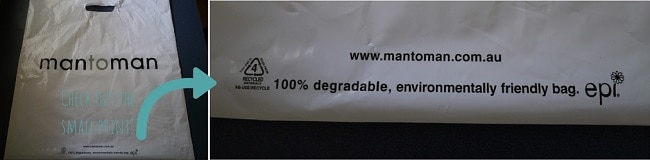

If there’s one environmental claim that makes me nervous when I see it printed on plastic-like products and packaging, it’s “biodegradable”. Why? Because without context, this label is vague and potentially misleading.

A one-word label like this tells us nothing about the true biodegradability of a product. What does it biodegrade into? Toxic or non-toxic? How long does the process actually take?

Yet companies plaster it on their products in an effort to make us believe they are more eco-friendly. As customers, we gravitate towards these products, as we want to make better choices.

Of course, some companies are diligent and can back up their biodegradability claims with real evidence. But others are not.

For the average shopper, it’s hard to pick out the good claims from the bad ones.

This post will help make some sense of it all.

What Does “Biodegradable” Mean?

Biodegradation is a chemical process in which materials are metabolised into water, carbon dioxide, and biomass by microorganisms. Depending on the material, toxic residues may remain.

The process of biodegradation is influenced by a number of conditions, including temperature, humidity, oxygen levels, presence of bacteria and time.

But what does “biodegradable” mean when it’s printed on packaging, or on the label of a product?

There is actually no single common understanding or definition of “biodegradable”, so different companies will mean different things when they use this label. That makes it pretty confusing for us.

We might assume that if a product is labelled “biodegradable”, it will be non-toxic, it will break down in home compost bins, and / or it will break down quickly.

But this isn’t necessarily the case.

The good news is, if a product is truly biodegradable, the company should be able to provide details supporting this claim.

And by details, I mean scientific evidence. Not anecdotal claims by the company CEO that they put it in their home compost bin and it “disappeared”.

Real data, based on actual laboratory tests.

Biodegradable Standards: What They Are and What They Mean

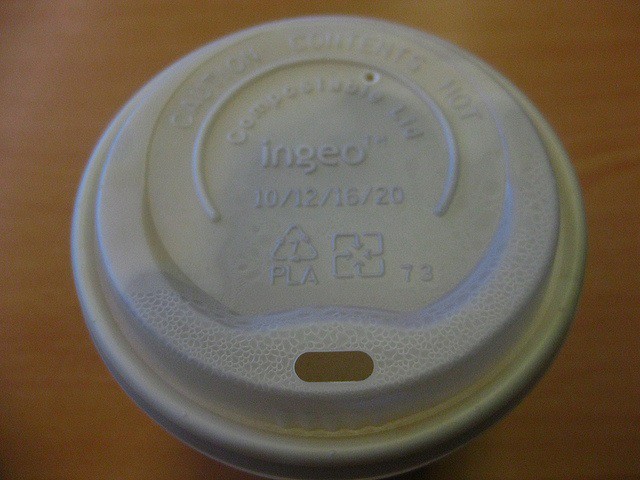

Because there are no defined understanding around what “biodegradability” means, certification schemes have been developed based on scientific standards and testing.

Certification is a way for companies to back up the claims they make about the biodegradability of their packaging and/or their products with scientific data.

Whilst voluntary, these schemes are attractive to companies wanting to demonstrate environmental responsibility and safety of their products.

As consumers, knowing that the packaging / product is certified gives us piece of mind, and helps us make better purchasing decisions.

These are the standards to look out for.

Standards for Biodegradable Plastics:

There are a number of different standards for biodegradable plastics, with different certification schemes established by different certification bodies. There is currently no standard with a clear pass/fail criteria for the degradation of plastics in sea water.

Standards for home composting:

These standards are awarded to products that will break down in home composting systems.

Look out for these numbers stated on the product or packaging:

Australian AS 5810 “Biodegradable plastics – biodegradable plastics suitable for home composting”.

Belgian certifier Vinçotte had developed the “OK compost” home certification scheme, requiring at least 90% degradation in 12 months at ambient temperature.

Labels proving home compostability are Vinçotte’s OK Compost Home, the DIN-Geprüft Home Compostable Mark and the Australasian Bioplastics Association (ABA) Home Compostable logo.

Standards for industrial composting and anaerobic digestion:

Standards for industrial composting and anaerobic digestion:

These standards apply to products that will break down in industrial composting facilities or anaerobic digesters within a stated timeframe. (This is not the same as home composting, and these products may not break down in home compost bins.)

Look out for these numbers stated on the product or packaging:

European Standards EN 13432 / 14995 (13432 applies to packaging only, 14995 applies to plastics generally);

The Australian standard AS 4736 which additionally includes an earthworm test;

ASTM D6400 is the US standard with clear pass/fail criteria;

Japan has no accepted standard, but certification scheme GreenPla is widely used.

Labels proving compostability in industrial facilities are the ABA Compostable Seedling logo, the Vinçotte OK Compost logo, the DIN-Geprüft Industrial Compostable Mark, and the Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI) Compostable logo.

The catch with these products is that not everybody has access to industrial composting facilities. Even when they do, the timeframes required to break down these products (typically 90 days) are often much longer than the timeframes these facilities use per composting cycle. In short, these products may not biodegrade at these facilities and some facilities will not accept them.

Biodegradable Products Aren’t Perfect

Even where a product is certified as biodegradable, that doesn’t mean it is 100% biodegradable.

For example, for a product to comply with EN 13432 / EN 14995 standards, at least 90% of the organic material must convert into CO2 within 6 months in controlled composting conditions; and after 3 months’ composting and subsequent sifting through a 2mm sieve, no more than 10% residue may remain (as compared to the original mass).

The Japanese certification scheme GreenPla specifies the minimum level as only 60%.

“Biodegradable” doesn’t mean there are no heavy metals or toxic chemicals present. Each certification standard has its own permitted levels of metals including copper, nickel, cadmium, lead, mercury, chromium and arsenic: US standard ASTM D6400 has the highest permitted levels.

And if there’s no commercial composting facility in your area, it will likely end up in the bin.

Where possible, it’s always better to avoid packaging altogether.

Is “Biodegradable” Labeling Regulated by Law?

With no mandatory standards on biodegradability: however, there are guidelines about how the term “biodegradable” (and other environmental labels) can be represented so that they do not mislead consumers.

In Australia, the Trade Practices Act (1974) requires businesses to provide consumers with accurate information about goods and services. Businesses that make claims such as biodegradable on their packaging must ensure these claims can be substantiated. It’s the law.

Being able to substantiate claims is particularly important if the claim predict future outcomes, such as whether plastics will biodegrade or within a certain timeframe and under certain conditions.

Claims about biodegradability must:

- Be honest and truthful;

- Detail the specific part of the product or process referred to by the claim;

- Use language the average member of the public can understand;

- Explain the significance of the benefit but not overstate it;

- Be able to be substantiated.

In Australia, the ACCC (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission) has taken action against a number of companies making misleading claims about biodegradability, including supermarket chain Woolworths.

Biodegradable Plastics: A Summary

Companies make unsubstantiated claims about biodegradable products all the time, sometimes deliberately but sometimes because they have a limited understanding of what it really means. Certification schemes are one way for us as consumers to pick out the good guys from the shady ones.

A product saying it’s “biodegradable” should specify what percentage the biodegradable content is, how long it take to break down, what it will break down into, and what conditions it needs to do so. (That’s what the certification labels are telling us.)

Look for products labelled “Home Compostable” first.

Bear in mind that even products that can be composted industrially may still end up in landfills, and biodegradable plastics do not break down in the marine environment. A plastic bag will still look like a jellyfish to a sea turtle, whether it’s certified biodegradable or not – and biodegradable does not mean digestible.

If biodegradable packaging ends up as litter, it can be just as destructive and harmful as conventional packaging.

Certified biodegradable plastics are better than non-biodegradable ones, but they are not the perfect solution. Refusing, reducing and reusing are always better options, where we can.

[leadpages_leadbox leadbox_id=1429a0746639c5] [/leadpages_leadbox]